It is basic Economics 101 stuff. When the housing market gets tight, when there are not enough existing homes on the market to meet the demand of buyers, new construction takes off. For the past few years, and especially since the pandemic began, the housing market has been as tight as anyone working today can recall. New construction has hardly been booming, however, and the lack of new homes has kept prices spiking. For the first time since before World War II, new construction is not keeping up with the needs of the market.

This phenomenon is a national trend that is more pronounced in Western PA. The root causes of the shortfall in construction are the same everywhere. Pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions have slowed construction dramatically. There are not enough skilled workers to build more homes. Lot inventory in virtually every city is too low to allow builders who want to expand to do so. Existing residents oppose changes in zoning that would allow for more new construction. Prices of land and new homes have increased to the point that first-time buyers – and many move up buyers – cannot afford new construction. These causes exist everywhere and several of them are exaggerated in metropolitan Pittsburgh.”

For most buyers looking at new construction, the dilemma can be summed up simply: if they can find new construction, they cannot afford it; and if they can afford it, the new home is not where they want to live.

It is worth remembering that home buyers choose existing homes over new construction by a five- or six-to-one ratio in any given year. For all the advantages of a new home – little maintenance, floor plans that you like, that “new home” smell – most homeowners are not willing to wait when they make the decision to buy a house. When there are not opportunities to find something acceptable in an existing home, new construction looks more appealing. The latter sentence describes today’s marketplace, but new construction is unable to meet the demand.

Fixing the problem is a tall order. Inflation requires counter measures that make it harder for the housing market, not easier. History has shown that cutting interest rates sparks the housing market, but rates will not be cut until and unless a recession occurs – and that carries its own set of challenges for the housing market. Local government leaders talk of making housing more affordable, but their residents typically reject measures that would lead to more density or lower cost housing in their communities (hence, not in my backyard or NIMBY). The reality is that we are experiencing market conditions that are at the extreme end of the cycle.

We have experienced extreme market conditions in the housing market before. Since the end of World War II, the most extreme imbalances have been in the opposite direction. Too few people were chasing too many homes. There were periods of overbuilding in the 1970s. Financial incentives drove housing bubbles in the late 1980s and mid-late 2000s. The latter bubble sparked a global financial crisis that left America with millions more homes than homeowners, and it took almost a decade for the market to rebalance. Balance did return in every case of overbuilding, and it will return again at some point in the next few years. In the meantime, buyers, sellers, builders, lenders, and real estate agents will have to adjust to a situation that is anything but normal.

What is Normal?

The housing market is like all areas of the economy. It is local. While there is an overall U.S. housing market that can be quantified and described, there are always local markets that are outperforming or underperforming the overall market. So, understanding normal means looking at what is going on in your backyard. That is especially true right now.

There are aspects of the housing market that are national (or global) in nature and influence the health of all local markets. The availability and cost of financing is one of these. Global supply chains, economic recessions, and inflation are others. Each of these is playing a role in dragging the new construction market down today. That is abnormal. In more normal times, the strength or weakness of the new construction market turns on local unemployment, demographics, existing home inventory, lot inventory, and home prices. Even in extraordinary times, like 2022, you can see how the differences in these regional factors influence construction. In cities with population growth – like Austin, TX or Orlando, FL – the drag from inflation and higher mortgage costs is less than in cities with declining population or unusually high home prices.

In Pittsburgh, it is clear that the abnormal conditions are weighing on the new construction market, but the impact of factors specific to Pittsburgh have been as influential. High inflation of residential building materials started in mid-2020, as did the lengthening of lead times for new construction; however, there were 13 percent more single-family homes started in 2020 compared to 2019, and four percent more started in 2021 compared to 2020. While both inflation and mortgage rates have created uncertainty in the Pittsburgh market, new construction will likely end 2022 within the range of what is the “new normal” for Pittsburgh. However, realtors and builders are in agreement that there would be more buyers for new construction were the financial conditions more favorable.

“It’s not a lack of demand for new construction,” says Jeff Costa, founder of Costa Homebuilders. “There are two reasons sales are slower. A dramatic increase of the cost of materials and labor has inflated the price of the home for the past two years. The other reason is that with the interest rates going up, people whose interest rates are affecting their monthly payment are having to pause their decision making.”

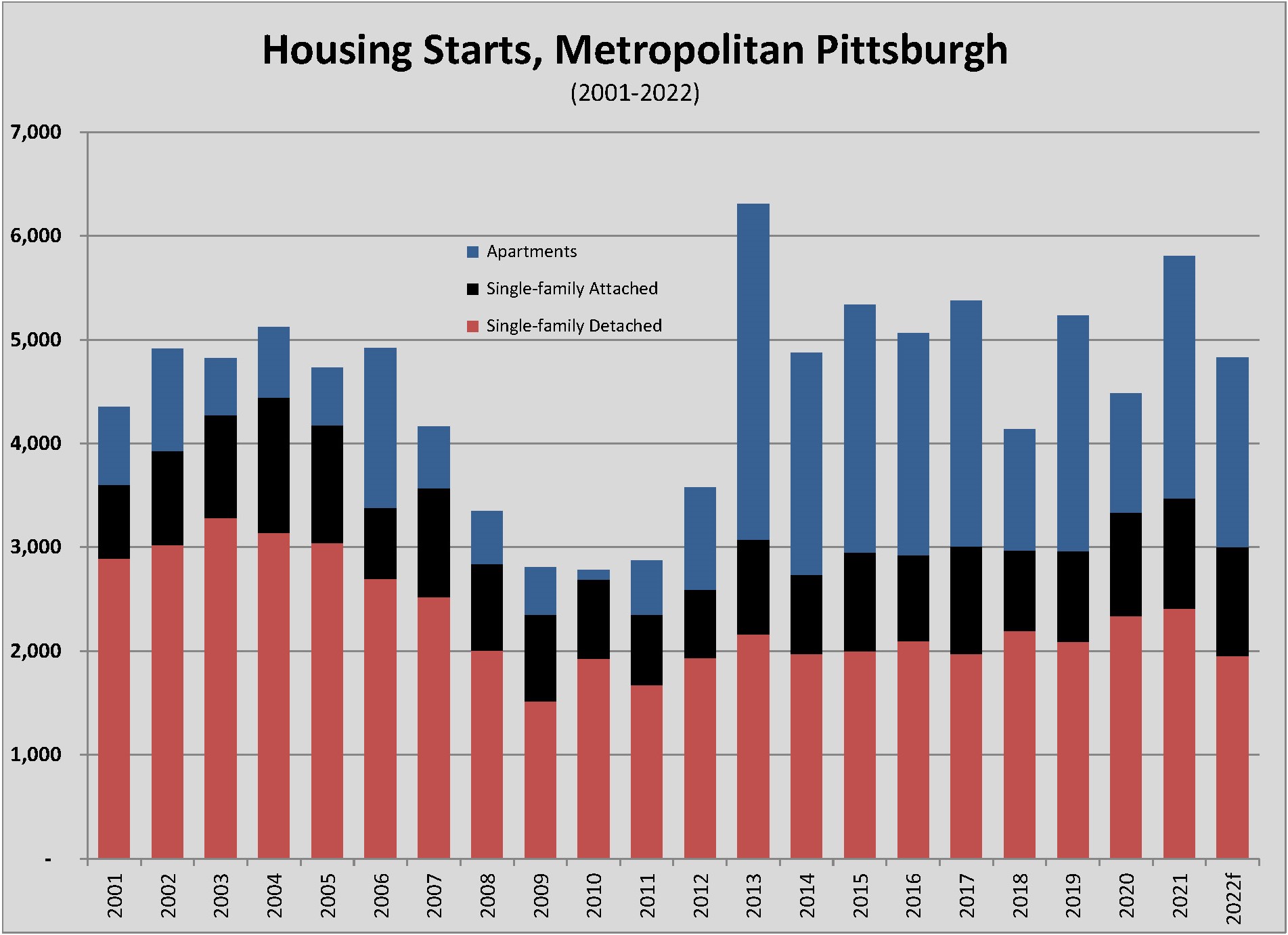

Residential construction saw activity step up significantly from the late 1980s to the mid-1990s. Driven by more rapid growth in suburbs in Butler, Washington, and Westmoreland counties, housing starts for single-family homes topped 3,000 units annually from 1995 until 2008, peaking at more than 4,000 new homes in 2003 and 2004. Following the mortgage crisis, new construction declined to fewer than 3,000 units again, topping 2,000 single-family detached home starts only twice from 2009 through 2017. Offsetting the decline in single-family homes was a mini-boom in apartment construction, which has averaged 2,125 since 2013.

In recent years, however, the strength of the Pittsburgh economy and its unusual demographics pushed single-family home construction higher. Since 2018, starts have bounced back to the pre-Great Recession era levels. This recovery to roughly 3,500 new single-family homes each year, including two years during the pandemic, came in spite of the limiting challenges of tight inventory and less land development.

Pittsburgh’s unusual demographics are playing a role in the higher volume of new construction in new normal years. The high share of older residents in Western PA gets plenty of press, but an influx of young people has altered the demographic makeup in an unexpected way. The growth of emerging technology companies has drawn enough young people to Pittsburgh that the median age of a city resident has fallen below 33 years old. That is seven years younger than the median PA resident and five years younger than the median U.S. resident.

The impact of this wave of younger people has been to fill up the thousands of apartments that have been built, mostly within Pittsburgh’s city limits. Given that the increase in apartment development is nearly a decade old, the wave of younger residents is also building the pipeline of prospective homeowners.

At the other end of the demographic spectrum, Pittsburgh’s outsized share of Baby Boomers (and their parents) has created a different pipeline of housing demand. Retiring Pittsburghers have long relocated to warmer climates after their careers ended. Empty nesters became a demand driver because they would vacate their long-time family home, creating opportunities for move-up buyers, and, if they stayed in the area, would become buyers of smaller homes. Firms like Weaver Homes, Scarmazzi Homes, and Traditions of America, have grown to be among the top ten builders in Western PA by building homes exclusively for empty nesters. But a significant change in lifestyle has made this demographic cohort a part of the supply problem.

While empty nesters can still be counted upon to downsize from their family homes, far more are remaining in those homes well past retirement. That greatly reduces the number of move-up homes available. Moreover, the number of empty nesters who own second homes – the so-called Snowbirds – has increased significantly. More than five percent of retirees own two homes, almost double the share in 2000. This means that another portion of move-up homes stay off the market in 2022 that would have been available in 2000.

These demographic and economic factors impacting supply and demand for new construction have added to the pressures on the market, but the most significant impact on new construction has been the slowdown in land development since the turn of the century. This slowdown also has a variety of causes, both economic and demographic.

The demographic factor has to do with the age of the developer in Western PA. Land development is a high-risk undertaking. Millions must be spent to acquire the land and prepare it for home lots. The process takes the better part of two years, meaning that developers may not see a profit on a new community until the project is four or five years into construction. The majority of residential developers in Western PA are owned by individuals over the age of 65. That is an age when aversion to risk is higher. Over the past decade, more developers have hung up their spurs than joined the industry.

One reason that the risk has become heightened is that the cost of development has increased significantly over the past 20 years. Land has become much more valuable, as the remaining undeveloped property in desirable communities has dwindled and competition for land – especially after the shale gas play began in 2005 – has increased. The cost of site development and utility infrastructure is roughly double what it was in 2000. And the time needed and cost added for entitlement and environmental approval has also increased markedly. Taken all together, land development is a more difficult undertaking than it was in the 1980s or 1990s.

“Land is getting more expensive with more regulations on development. There’s not a lot of flat land left so you’re dealing with slopes. They just brought back federal clean stream regulations that affect how we develop, adding thousands of dollars per lot,” explains Paul Scarmazzi, CEO of Scarmazzi Homes.

Development in the New Normal

Scarmazzi is one of a few builders who choose to develop its own communities. During the 1990s, dozens of custom builders fueled the boom in construction in the suburbs. Developers could count on builders taking down 10 or 15 homes per year in these kinds of communities. As time and economic woes have sapped the ranks of custom builders, a developer of a potentially large community – one with several hundred lots – faces the prospect of managing multiple builders over a decade’s time. Today, the region’s top two builders – NVR Inc. and Maronda Homes – account for 50 percent of the total starts. Developers have understandably shifted their focus to new projects for the production-style builders that allow them to complete the project within a three-to-five-year period, although the chill from the higher prices and mortgage rates have slowed sales for production builders too.

Like Scarmazzi Homes, Weaver Homes and Traditions of America also develop the communities in which they build homes. Custom builders like Barrington Homes and Eddy Homes, which moved away from development until recently, are finding it necessary to develop in order to maintain the supply that their customers demand.

“We’ve changed our business model to focus on building on the customer’s lot. I’m getting into larger houses more each year so I’m building fewer homes on larger lots,” says Costa. “There will also be lots becoming available from developers who have sold to the bigger production builders. Those builders are seeing their sales slip too.”

While Foxlane Homes may be relatively new to the Pittsburgh area, they are not new to the industry. Partners Mike McAneny and Eric Nicholl, industry veterans, are taking a hybrid approach to finding supply, utilizing a mix of raw land and finished lot projects to add inventory in an increasingly competitive market. Foxlane entered the market in 2021 by building out some remaining finished lots in Hampton and selling out a small plan in Sewickley, but now they are active in four new communities across Pittsburgh, with many more in the works.

“One of the advantages that Mike and I have is our experience in both building, entitling and developing our own lots. We are not rule-bound by a particular way of operating. We are not purchasing only finished lots or purchasing only raw land,” Nicholl says. “We have flexibility and experience to do either with the right project. And, with Mike being a native to Pittsburgh’s North Hills, we have been able to lean on some of his long relationships with developers, vendors, and sellers to help grow the brand.”

“Additionally, we have flexibility to take on large or small communities in the right locations for the Foxlane brand. Nowadays, it takes much longer time to get a large piece of property approved and to the market, so we can do some smaller infill properties to fill the gaps. We are very particular with our locations and projects to ensure we protect the Foxlane brand by building in locations where people want to be. However, we are not limited to the size of a project or the complexity,” Nicholl says.

Finding opportunities to build where people want to live is no small challenge. Darlene Hunter, vice president, New Homes Division of Howard Hanna Real Estate Services, sees the market as delineated between the buyer for production-style homes and custom homes. While buyers still have to hustle to find available new construction in the larger Ryan Homes or Maronda Homes communities, the market for the buyer who wants a true custom home is most challenging.

“We have buyers that can’t find what they’re looking for in the market or price point that they’re looking for,” Hunter says. “They want new construction, but it may not exist where they want it. Most of the custom builders in our markets are $700,000, or $800,000, or even up to a million dollars in these custom home communities. Pricing and product availability are limiting what people can buy in the custom home market.”

Hunter says that the lack of land development in the region’s most desirable municipalities is part of the problem, but she also places blame on the conditions that have been warped by the pandemic.

“The builders have had to deal with the supply chain and labor shortages to concentrate on completing the houses that are under contract, instead of focusing on building spec homes,” says Hunter. “I believe if there was inventory, people would buy that inventory because there would be an established price. That’s especially true for the people relocating into our marketplace.”

While it is clear that the number of available lots to build new homes is significantly lower than in 1995 or 2000, there has been inventory built during the post-Financial Crisis period. Following the global mortgage market meltdown in 2008, regulations added by the Dodd-Frank Act made development of new communities more difficult and expensive. Lenders wanted little or nothing to do with development loans, and only slightly more appetite for speculative building. Lot inventories became depleted without a new pipeline. In Cranberry Township, for example, the total number of lots and units to build fell to 510 in 2017. Only 159 lots remained unbuilt that year.

By mid-2022, however, the total number of lots and units swelled to 1,079 and 817 – or 76 percent – remained unbuilt. One thousand available lots/units would have barely satisfied demand for one year in Cranberry Township in 1990. Similar dynamics exist in other municipalities where land is still available, like Pine Township, Cecil Township and Adams Township. The market in 2022 is slower but clearly demand is as much to blame for the low volume as tight supply. The daily drumbeat of negative news and the shifting rate environment are paralyzing decision making for many buyers

“I feel like consumer confidence is a problem that is holding people back. I don’t think people are certain where the economy is going. The media has to report what is accurate but sometimes I think the sensationalism of the way it’s reported gives people pause and prevents them from moving forward,” Hunter says. “But I think people are still looking to buy new construction so, if things stabilize in the next quarter or into 2023, buyers will move back into the market, and I don’t think interest rates will hold them back.”

Lenders have responded to the escalating rate environment by being creative, offering improved terms and conditions for qualified borrowers. There appears to be some relief on the horizon for inflation, although the shortage of skilled workers may force builders to keep prices higher, even as costs for lumber, metals, asphalt, roofing, and other products have declined. Conditions for land development are not going to improve significantly in 2023, which means the opportunities for new construction product will be limited through 2024.

Taking all the factors in the market into account, Pittsburgh is going to be a tough place for new construction for the first-time buyer, unless that buyer is shopping above the $500,000 mark. For move-up buyers, the market will require them to spend a bit more and to be patient about finding new construction in the municipalities that are in high demand.

“We believe we are still under-supplied in Pittsburgh,” says Nicholl. “Buyers are more discerning now. We are seeing buyers looking for well thought-out floor plans, higher quality finishes, and the ability to customize or personalize their home. However, the property has to be in the right area and positioned properly to the market.”

“I think as soon as inflation and interest rates settle, things are going to be moving again, whether that’s 2023 or 2024,” predicts Costa. “When things have stabilized, and rates are down a little bit, there are still lots of people that want new construction.” NH