If you are a homebuilder working in Western PA, you probably feel like you have been sailing against the wind for more than a decade. Although virtually no regional builders were caught with too many spec homes when the mortgage crisis hit in 2007 and 2008, the business of new construction became more difficult in the aftermath. Regulatory burdens increased. The inventory of lots for new homes shrank and little were developed to replace the ones that were taken down.

The 2010s were a tough decade, but as it ended there was a breeze beginning to form at the backs of the residential construction market. New development began to return. Interest rates stayed low. Millennials were beginning to enter the market in a big way. Then came COVID-19.

Some 18 months after the first infections were detected in Western PA, the market has fared better than was feared in March 2020. After an initial mandated shutdown of homebuilding sites, builders were able to resume work and finished the year in better shape than in 2019. In fact, construction of single-family homes reached a post-Great Recession high of 3,337 new homes. Today, buyers still outnumber sellers and there is barely one month’s inventory of existing homes for sale. Interest rates remain below three percent for 30-year mortgages. But one nagging problem has been a headwind on new construction sales since mid-2020: inflation.

In the early spring, as vaccines became widely available throughout the U.S., demand for goods and services soared as businesses were able to re-open fully. For the homebuilding and remodeling sector, however, demand was ignited when businesses shut their doors and people were forced to work from home. A veritable residential spending boom occurred last summer that has lasted until today, pushing residential construction higher by almost 25 percent than in the 12 months before. The spring 2021 boost to demand, on top of the higher demand for building materials and products, created supply chain disruptions that have driven inflation to levels unseen for decades. That makes residential construction more difficult to plan and estimate. Ultimately, higher inflation creates an uncertain environment for homeowners and home builders.

Perhaps because of the tailwinds pushing the housing market forward at the end of the 2010s, the impact of inflation has been more muted than expected on new home construction. Rapidly rising prices have certainly had an effect but, thus far, seem to have pared back home building only slightly across the U.S. In Pittsburgh, any paring back has been negligible.

Heading into 2022, three main questions remain unanswered about inflation. Will prices return to the cyclical norms once the supply chain is restored? Will the supply chain be restored to normal? And when will that happen? The near-term positive trend in new construction may depend upon how those questions are answered.

Lumber, Pandemic, and the Sources of Inflation

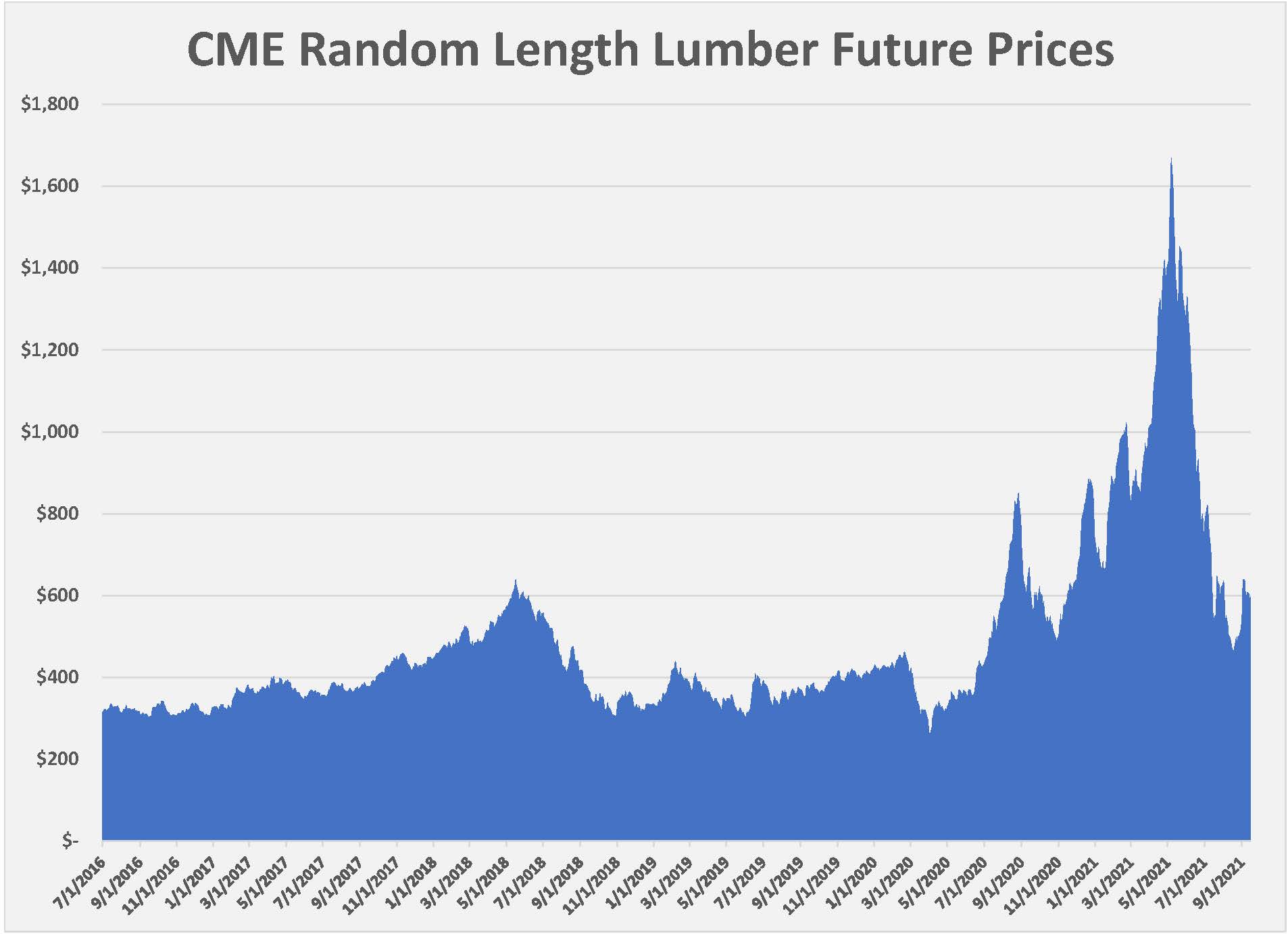

Lumber – specifically softwood lumber used for framing, plywood, medium-density fiberboard (MDF) and oriented strand board (OSB) – has been the poster child of building material inflation. The commodity traded at the lower end of a $300-to-$450 per thousand board foot range for most of the last 30 years. That meant the lumber package, which covered the framing and sheathing, for the average home was around $20,000. Lumber was still priced in that range until it jumped to $400 in mid-June 2020. From there the price skyrocketed to nearly $900 in August, before falling back below $500 in November. Just a few months ago, prices spiked twice as high, reaching $1670 per thousand board feet on May 7.

The spike in lumber coincided with a red-hot housing market in general. Home price appreciation topped 20 percent in many markets. By late spring, the price of a home and the skyrocketing prices of new construction materials chilled the market. Buyers went back to the sidelines and the price of lumber fell precipitously, hitting the $500-to-$600 range by late September.

Lumber’s runaway inflation was the product of a perfect storm of bad luck, poor timing, and unforeseen consequences of decisions made ahead of 2020. Like most supply chain problems, the issues were exaggerated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

There is a long-simmering trade dispute over soft wood lumber between the U.S. and Canada. Dating back to 1982, the dispute has waxed and waned. The differences between the two countries have settled by several agreements, including NAFTA and USMCA, but a Trump administration tariff of 20 percent remains on Canadian soft lumber delivered to the U.S.

The pre-existing condition impacting supply started at the beginning of the 2010s, when a Pine Beetle infestation in British Columbia began killing large swaths of Western Spruce trees. There are estimates that as much as 60 percent of the soft lumber comes from western Canada. For timber companies, the beetle infestation wasn’t all bad news. The suppliers harvested the dead standing timber for years but by 2019 the dead trees still standing were no longer viable. At the same time, in the U.S. the growth of southern cities created opportunities for landowners to sell property to residential developers at a higher price than lumber companies would pay for timbering.

What might have been a minor supply chain disruption became a crisis when COVID-19 hit North America. Multiple timbering operations were shut down for weeks at a time because of COVID-19 outbreaks. As supply lines were disrupted, American homeowners began a spree of remodeling and additions, driven mostly by the experience of sheltering at home. Residential investment increased by more than 25 percent year-over-year.

“I don’t think there is just one root cause. The virus is part of it but there were a couple of other things that contributed to it,” says David Jones, president of Brookside Lumber. “When the virus came along the news made it look like the end of times. People held on to cash. All the mills that should have been cutting logs and processing the lumber, and all the distribution channels that put that lumber into our hands stopped hard-and-fast.”

Jones notes that when things re-opened in late spring 2020, demand roared back and has not abated since. He explains that while the commodity price for lumber has plunged, the price that distributors need to sell has changed more gradually.

“The problem for the industry is matching the price between the inventory on the ground and what is coming. When we order railcars of material from the West Coast, they take about five weeks and are priced at the time of order. The problem was we were seeing 10 to 20 percent drops in the market price per week. That meant the market price for material we ordered was half of what it was when it was delivered,” Jones explains. “Our philosophy is to average somewhat between what we have and what the market is. We tend to be a little heavier on the in-stock position, which is a good thing on the way up but a bad thing when prices are coming down.”

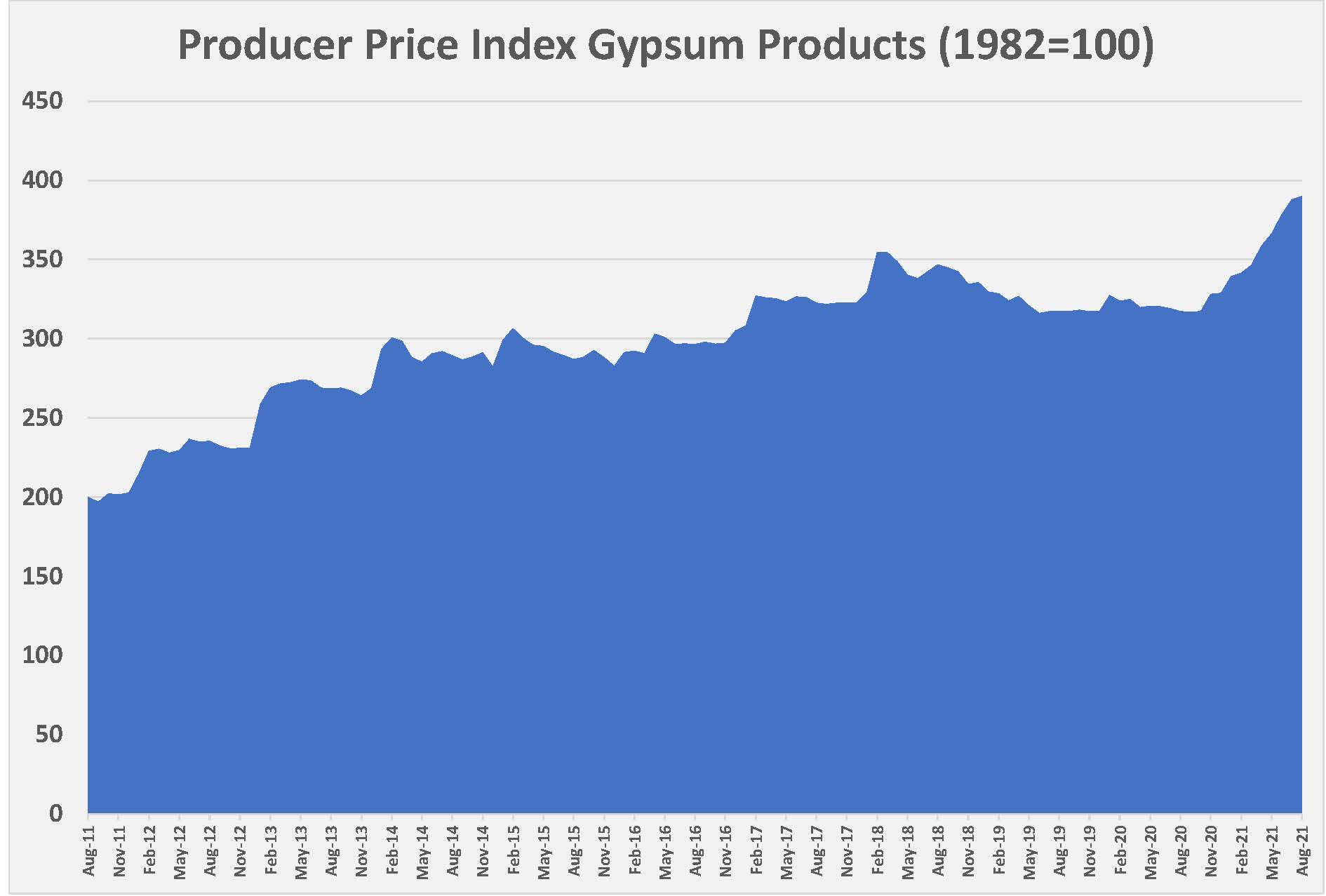

While lumber received the most headlines for its meteoric rise and fall, it was hardly the only building material to experience high inflation. Even as the price of lumber tumbled back by two-thirds by fall 2021, prices of many materials and products remained elevated compared to one a year earlier. Steel is more than twice as expensive, which affects the cost of concrete reinforcing (which is used in foundations and slabs in homes) and heating and air-conditioning equipment. Copper, which is used in residential plumbing and electric wiring, is 50 percent higher. Aluminum is one-third higher. Drywall and its related products are 21 percent higher. Plastics and vinyl are 26 percent more expensive than a year before. And fuel is more than 80 percent inflated compared to fall 2020. That adds to the cost of everything that is shipped to the builder or its distributors.

“What’s happened since lumber has come down, although it is still probably double what it was 18 months ago, is there are shortages and price increases almost across-the-board on other products,” says Jeff Costa, founder of Costa Homebuilders. “In general, our prices have plateaued since May. The costs have not. People think that our prices should be coming down because lumber came down, but unfortunately the other prices have gone up.”

Inflation, as an economic concept, is fairly easy to understand. Like all things economic, inflation is a product of supply and demand. When demand exceeds supply, prices go up. If demand exceeds supply for an extended period, or by an excessive amount, prices stay up and create an inflationary cycle. Such cycles happen regularly in limited sectors of the economy. Those cycles self-correct when high prices chill demand or attract more suppliers to the market. China’s booming economy added to the demand for energy to such a degree that oil and gas producers could not keep pace in the mid-2000s. Oil reached $144 per barrel in 2008. The price was an incentive for producers to increase drilling and the shale exploration created a glut by 2014, and prices plunged to $27 per barrel.

The difference in the marketplace today is that an artificial factor, a global pandemic, is preventing the suppliers from responding to the increase in demand. As COVID-19 surges and dissipates at different rates throughout the world, manufacturers and raw material suppliers have seen their outputs rise and fall erratically. The supply chain has become disintegrated to an extent not seen before in the industrial era. Shortages of even limited components – like microchips – can grind production of major consumer and capital goods to a halt. Because COVID-19 has surged at least four separate times, with each surge occurring at differing times in different parts of the world – there has been no opportunity yet for the supply chain to recover and meet the pent-up demand. For all the handwringing that is done about the Federal Reserve Bank’s fiscal stimulation, the real cause of inflation has little to do with the money supply. Many more people want cars, appliances, lumber, and new homes than there are suppliers to sell them. Prices had to go up.

Supply Chain Problems Are New Construction Problems

What is not clear is the degree to which inflation has slowed new residential construction. Thus far, the impact has been uneven. The residential new construction market is made up of two components, single-family and multi-family dwellings, and the motives behind the construction of each one differs. The inflation impact has also differed.

Multi-family projects are financed by investors who provide equity for between 65 percent and 80 percent of the project cost, depending on the lending conditions at the time. Those investors expect to receive cash flow income from rents that exceed the debt service, plus the benefit of having the debt paid by the tenants over time. There is also the expectation that the value of the property will appreciate over the time that the investors own the property. Investors typically expect between 15 and 20 percent return, on an annualized basis, by the time the property is sold.

Single-family homes are mostly owner-occupied and financed by a long-term mortgage. The motives for building a single-family home are varied but ultimately boil down to the owners wanting more space in a location of their choosing. The return on their investment is largely emotional while the owner occupies the home. The financial benefit occurs when the home is sold for more than the homeowner paid.

Through the prism of those respective motives, the impact of the rising lumber prices is quite different. For single-family homes, the increased price may be offset by reducing other aspects of the planned home – ranging from amenities to size – or because the builder absorbs the higher cost. Moreover, the pain point for the decision to build a single-family home is the mortgage. If the homeowner can afford a higher monthly payment that higher lumber prices dictate, the project will still happen.

The decision-making process for apartment construction turns on the pro forma income and the expectations of return on investment by the owners. Single-family homeowners have good reason to watch costs during construction but the risk for controlling them lies with the builder. For multi-family construction, the duration of the planning and construction cycle is much longer. That elevates the risk of price changes that occur during the planning and pricing of the project. Should the costs of construction rise to levels that decrease the expected income sufficiently, the decision to proceed will be delayed. For that reason, many multi-family projects were deferred, at least temporarily, this past winter and spring, even though the demand for apartments remained red hot.

As the summer unfolded, and lumber prices cooled, many of those projects came off the shelf and construction of new units climbed higher. From a low of 365,000 units (on an annualized basis) in February, construction of privately funded multi-family housing has increase in all but one of the following five months, reaching a peak of 474,000 units in July.

Conversely, because the gestation period of a single-family home is so much shorter than an apartment project, the decision making has more closely followed builders’ costs, which have remained much higher than wholesale or futures prices. New housing starts plunged to 685,000 homes in April 2020, only two months after finally reaching the million-home mark for the first time since the mortgage crisis crashed new construction in 2007. But new construction rebounded sharply in June and July to more than 1.1 million homes each month, suggesting that prospective home buyers were adjusting to the market as the headlines about the soaring lumber prices went away. That data matches up to the experiences of the local professionals.

“What happened was there was a window of time when builders just stopped building, or at least stopped selling, because it was that outrageous,” recalls Costa. “I was on a national forum with builders all over the country and a lot of them just told their salespeople to stop for 30 days.”

Costa says his sales have not slowed, even if buyers may have taken longer to pull the trigger in the spring.

“We were starting to hear some rumbling about starts slowing back in April and May, which was about the high point for prices. But smart builders have escalation clauses built in and are applying them where they need to,” observes Jones. “I don’t think the price has had an impact on starts. I think what’s influencing starts now are lead times on products. We’ve got a very broken supply chain. It’s a little surreal at this point.”

Most Americans can identify an incident where that supply chain disruption has impacted their purchasing over the past year. In any given week, there will be a shortage of some consumer good that was readily available in 2019. Residential construction consumes materials and products across a wide spectrum, utilizing commercial, industrial, and consumer goods. While there are shortages in commodities that are making it tough to keep construction going, the real headaches have come from manufactured products. The holdups in production are being caused by shortages of materials, subcomponents, and skilled labor. Whatever the reasons, the disruptions have lengthened lead times on many items critical to maintaining progress on construction of a new home.

“Last year was very difficult for residential. We had no lead times last year when the pandemic hit because nothing was coming,” recalls Tom Baney, president of Standard Air & Lite, a supplier of heating and air-conditioning equipment. “Carrier adjusted their lead time from 14 days to 100 days. We recalibrated our buying accordingly. So far Carrier is telling us that they are not going to pull back on that any time soon.”

Baney says that in response Standard Air & Lite greatly expanded its inventory. That strategy gave it a competitive advantage over suppliers that depend more upon manufacturers for tighter logistics, but it also represents a greater risk in the event the market slows unexpectedly.

“We have long lead times on windows and cabinets, and very long lead times on appliances. Anything with resins has been a problem, so vinyl, plastics, and adhesives. Steel has been very high in price and in short supply. That affects appliances. That also affects us with our steel trusses and steel plates,” Jones says. “Windows traditionally have a four-to-five week lead time are now 14 weeks.”

“Builders don’t want to put a hole in the ground and start the clock ticking until they have all their ducks in a row,” he continues. “Builders are trying to order further out and get their long lead time items lined up earlier in the process. That means the end user has to make their selections a lot earlier.”

Homebuilders have shifted gears to manage the uncertainty of delivery times. For the most part that has meant managing the expectations of the homeowners, many of whom are not experienced in the process. In addition to getting decisions made earlier, most builders are extending the construction schedules they quote to customers.

“It comes back to blocking and tackling, communicating with the customer. If you can set the expectation with your customers up front – which we’ve had to get better at doing – and keep them informed, you can control the controllable,” says Liam Brennan, vice president of Infinity Custom Homes. “The earlier we can finalize selections, and not change them, the better likelihood that we can get things ordered and in on time and have a better chance of maintaining the schedule we’ve presented. We shifted our processes forward in the construction cycle.”

Infinity employs a dozen selection managers who guide homeowners through the process of choosing dozens of materials, fixtures, and appliances. Brennan says that there has not been a need to add to that group, but Infinity’s management has increased the support provided to the selection team.

“We’ve done a lot of training. We have a lot of weekly meetings to update them on what lead times are changing. At the end of the day it’s just requiring clearer communication,” he says.

Ryan Homes, the Pittsburgh region’s largest builder, has an extensive supply network and operates in a production style. To navigate the current environment, Ryan Homes is building 30 or 60 days extra into the schedule for a new home, which the company can often deliver in a few months. Construction of a Ryan home is not taking any longer but the company has added time to the front end, forcing decisions that are typically made after construction starts to be made at the time the contract is signed.

Custom builders generally take a few months longer to build a home than a production-oriented builder. While that might give a custom builder more of a window to secure decisions from its homeowner, custom homes imply a broader selection of options and products. That increases the risk to the builder that the customer will be looking for something that cannot be procured in a reasonable time frame. Brennan notes that building larger houses gives Infinity a longer runway to adjust; therefore, construction schedules have not extended much more than a month. Jeff Costa says that has added months to his delivery time.

“The shortages are definitely hitting us. I have houses framed with no windows that have been sitting for two months. Demand went up and manufacturing can’t keep up,” Costa says. We’re still getting calls, but we used to tell people that we could build a house in eight months and now we’re telling them 12. It’s a matter of setting realistic expectations. I built a house for a customer during the coronavirus in seven months. If that was today, I would never be able to do that.”

Choppy Waters in 2021 Will Lead to Smoother Sailing in 2022

For all the challenges associated with the market conditions and supply chain in 2021, new construction is still accelerating in Pittsburgh. Through August, new residential construction was up 8.1 percent compared to the same period in 2020.

Single-family detached construction was up even more, with 1,557 homes started from January through August, an 11.1 percent jump. A closer look at the data reveals that the comparison reflects real growth, as the March-April 2020 shutdown of residential construction has been worked through by the end of August 2020. Builders are on pace to top 3,000 single-family units in 2022 for the first time in more than 15 years. The market is healthy and builders are responding.

Inflation should only have a significant impact on residential construction if it remains stubborn or if the higher costs of living spark an upward cycle of wage increases. The current spike in inflation has been tied to the COVID-19 pandemic and its peculiar impact on the global economy. That peculiar impact should lessen when the pandemic recedes. The most recent reading on consumer inflation suggests that the spike in pricing has flattened. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported on September 14 that the consumer price index rose only .03 percent from July to August, lower than expected. Moreover, the core consumer price index (which strips out volatile energy prices) moderated to 4.0 percent year-over-year. Put into perspective, core consumer inflation ranged between 3.5 and 5.0 percent throughout the Clinton-era economic boom of the mid-1990s and was 4.4 percent in December 2007. The U.S. economy has thrived during moderate inflation before.

In the final analysis, residential spending tends to have a longer time horizon than most consumer purchase decisions. People buy homes for the perceived value over many years. The average period that a person owns a home now exceeds 10 years, for example. Moreover, the current trend in home appreciation suggests that the value of new construction will not decrease even in the short term. Home builders are skilled at minimizing the impact of temporary or limited inflation. Low interest rates help offset the increased costs of home ownership when that is not possible.

With growing evidence that Millennials and Gen Z renters are anxious to own homes, there is pent up demand for inventory. Baby Boomers have proven to be more reluctant to leave their family homes than previous generations have, and they are living longer too. All of this means there will be demand for new construction that will be tough to hold back. By mid-2022, the biggest challenges for residential new construction should again be limited lot inventories and worker shortages. After two years of unexpected inflation and uncertain supply lines, builders will likely welcome those challenges again. NH