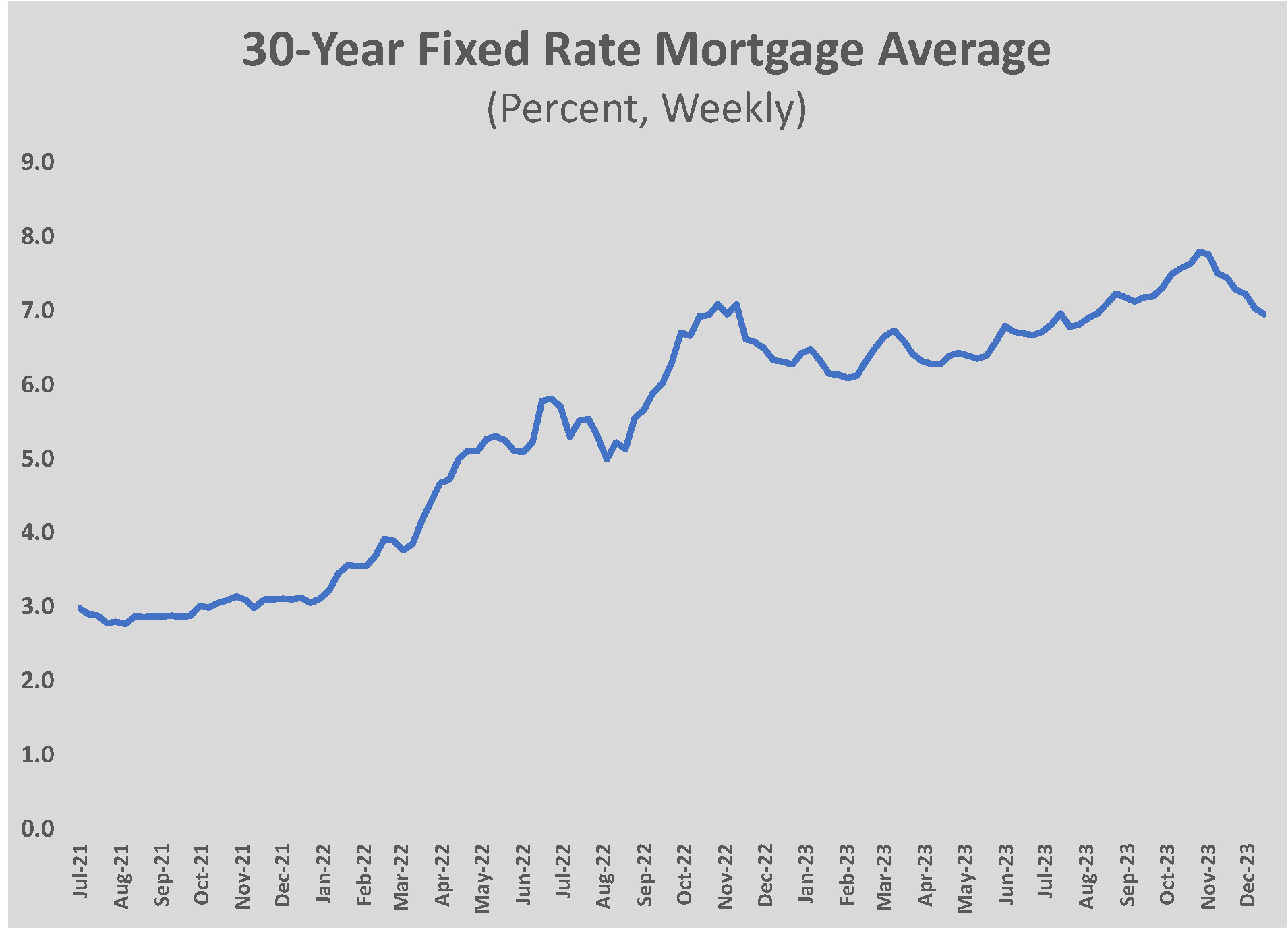

That upward trend accelerated again this summer, after the Fed paused its hikes, making home ownership less affordable than it has been since after World War II – including in 1982 when the prime rate topped 18 percent. After increasing by a full percentage point throughout the third quarter, mortgage rates have been falling and most observers believe the reversal marks a break for borrowers that will continue beyond 2023.

The bad news, however, is that the forecast for 2024 is not necessarily rosy. The Federal Reserve Bank’s Open Markets Committee forecasted three rate cuts in 2024. Wall Street has begun to predict that the central bank will cut rates before mid-2024, with several global banks expecting the Fed to cut rates by two percentage points by the beginning of 2025. For long-term interest rates, like 15- or 30-year mortgages, other market factors are keeping upward pressure.

It is worth noting that the current elevated rate environment is roughly where mortgage rates have been historically. While it is true that mortgage rates above seven percent have been rare, so have rates below five percent. The extended period of near zero rates that has existed since 2009 has left Americans shocked to see mortgage rates with a seven in them. That’s especially true for people under the age of 40. Thus, for first-time buyers, the current environment feels especially hostile and expensive.

Higher borrowing costs have squeezed a significant share of buyers out of the housing market over the past 18 months. High rates are a disincentive for sellers too, who would have to trade a low-rate mortgage for one that is three or four percentage points higher. Declining mortgage rates will be a welcome sight for the housing market. It seems certain that there will be downward pressure on mortgage rates in 2024. It is less certain how strong that pressure will be.

The Forces Increasing Rates

It is possible for two opposing ideas to be true at the same time. The Federal Reserve Bank does not raise mortgage rates; however, by raising its overnight lending rate – the so-called Fed Funds rate – the Federal Reserve creates upward pressure on all lenders. And that eventually pushes mortgage rates higher.

Part of what drives mortgage rates higher is the supply and demand for mortgages as investments. The majority of mortgages originated in the U.S. are not held until repayment but are instead sold to investors, who employ servicing companies to collect payments each month and keep the interest as a yield on the investment. This is known as the secondary market for mortgages. The largest buyers of mortgages in the secondary market are the government-sponsored enterprises (GSE), Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which support 70 percent of the mortgage market by purchasing residential loans (and their associated risk of default) from private lenders. There are also private investors in residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS). The volume of private-label RMBS is more volatile but typically is above $100 billion annually.

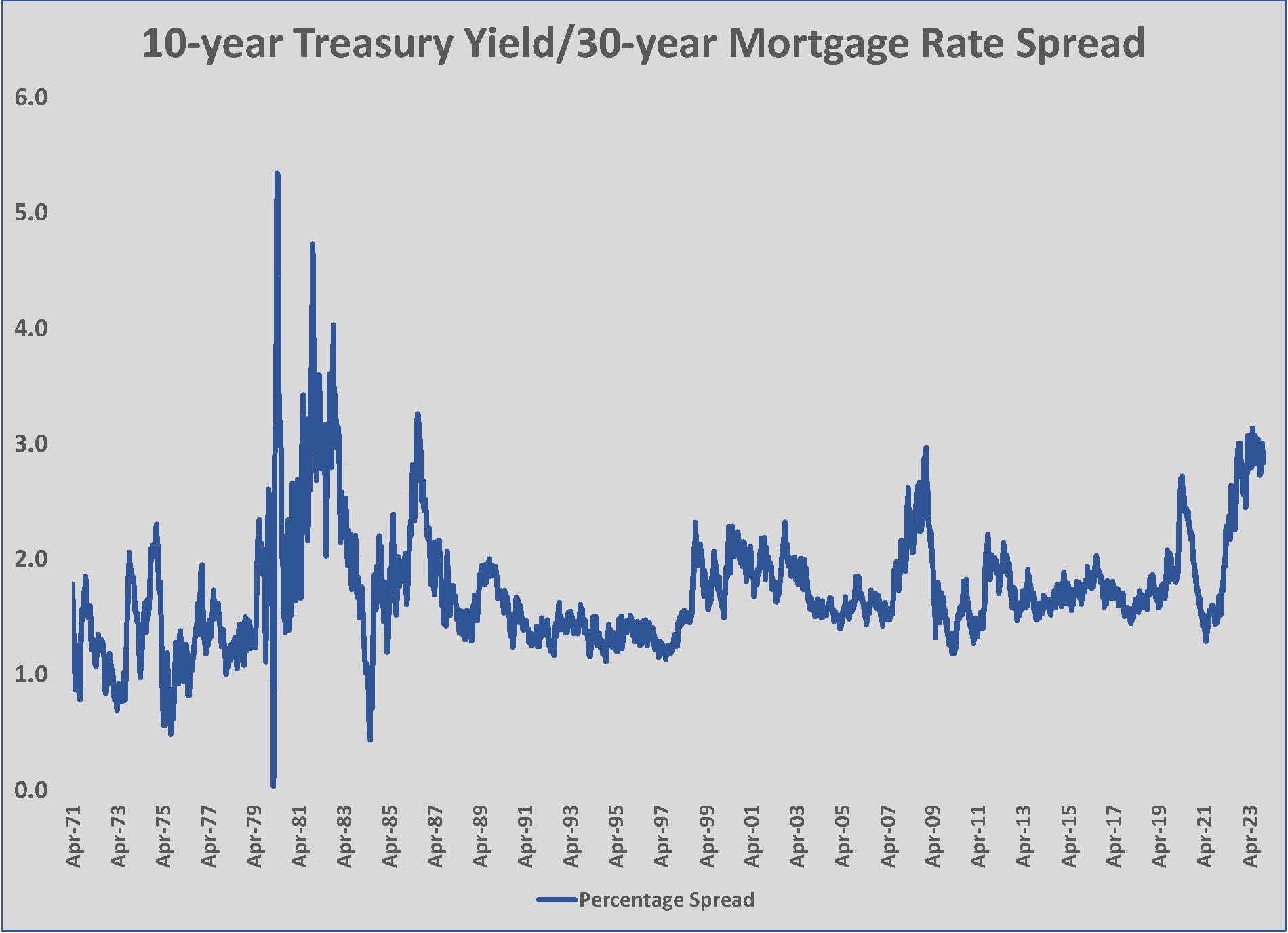

Both the GSEs and private investors rely on capital to fund their purchases. With long-term rates for government-backed bonds and Treasury notes floating higher, investors can receive yields that are in the five percent range for no risk. That creates competition for investment capital for securities like RMBS and forces the lenders to offer a higher spread, or risk premium, to make residential mortgages more attractive. That higher spread is passed along to the borrower in the form of a higher mortgage rate. It is this market pressure that has driven rates higher since mid-summer 2023

The good news for 2024 is that there is ample evidence that the returns on relatively risk-free investments like Treasury bills will be falling. In spite of strong economic data, most of the forward-looking economic measures are indicating that the economy is slowing, which will help the Fed ease monetary policy. Moreover, as the economy slows, investors flock to safer havens like U.S. Treasury bonds, which offer lower yields as demand increases. That helps ease the pressure on other long-term debt, like 30-year mortgages.

The federal government can also pressure rates indirectly through its oversight of lenders. Banks that are part of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), lenders that participate in the secondary market (even if they do not sell to Fannie or Freddie), or that fall under the purview of the Federal Reserve Bank, are subject to federal regulation. Since the Great Depression, regulations have tightened and loosened in response to market events but have always exerted an influence on mortgage rates.

Federal influence on rates can be direct, such as in periods when the GSEs set standards that purposely limit or expand the size of the market. If Fannie or Freddie reduce the minimum credit score or increase the loan-to-value ratio, for example, more people qualify for mortgages. Those agencies also have a direct impact on the cost of lending when they make regulatory compliance – the paperwork associated with lending – easier or more difficult.

The latter is often overlooked by borrowers as an influence. In periods of higher regulatory pressures, lenders must spend more time on each loan. Lenders invariably must add staff to comply with the additional regulations and to verify that compliance. Additional time and overhead means the lender’s cost of each loan is higher; therefore, the amount of money the lender charges the borrower over and above the base rate of interest to cover its overhead and profit – referred to as the spread – will increase.

“Easy access to and from the city is tunnel free and commute times are relatively brief,” he added. “It is here that the crossing of Interstate Routes 279 and 79, Routes 19 and 228, the Pennsylvania Turnpike and other major roadways occur along with short routes to Pittsburgh International Airport. Casual and formal dining options, entertainment and shopping establishments, and service businesses find this a growing and profitable area, one that offers a distinctive location.” And just as distinctive is Heurich Homes latest construction project currently in its third and final phase – Mallard Pond in Marshall Township. Here, one-of-a kind, custom designed homes feature upscale, private building lots on a cul-de-sac street with large, flat backyards that flow mainly into heavily wooded open space. “This offers a place for swimming pools and other types of outdoor living spaces that are so very popular today,” he continued. “A paved, six-foot wide walking trail is just now being constructed that continues from our sidewalk system into 37+ acres of our wooded open space.” With Phase 3 home prices starting at $1.6 million, specialty features such as sunken areas that house golf simulators, are not uncommon. The homes often feature a second study, flex room or guest suite on the first floor. “Exterior lighting is very popular along with extensive landscaping, hardscaping and lawn watering systems,” he said. “As a truly custom builder, our homes are unique and have endless possibilities.” In business since 1972, Heurich Homes incorporates the latest proven technologies, eco-friendly construction and construction management, ensuring cost and energy efficiencies along with technologies that benefit various home systems over the life of the building.

The regulator’s requirement for banks to maintain reserves against potential losses from loan defaults is also very impactful on the mortgage market. This regulation requires that banks hold a portion of their cash deposits to protect against loan defaults. While this regulation has existed since the Great Depression era run on the banks, the reserve requirement has been increased or cut depending on the market conditions. After the mortgage crisis in 2008, reserve levels were increased significantly, and the leverage banks could deploy (the multiple of deposits that could be loaned) was cut. The result was a steep decline in the amount of credit available for mortgages. Fewer people could get mortgages.

Today’s conditions are hardly as dire as those of 2008; however, regulators and lenders seem to have remembered the hard lessons of that era and are tightening standards and asking for more interest for mortgages. The latter will keep upward pressure on mortgage rates, even as the Fed cuts rates in 2024.

Still, history has shown that when the Fed begins cutting rates, mortgage rates begin to follow within six months. That is especially true if the 10-year Treasury bill follows the Fed Funds rate, which is currently the case. Just prior to Christmas 2023, the 10-year Treasury broke below four percent. The average rate for a 30-year mortgage also broke below seven percent. That three percentage point spread between the two is atypically high. Since 1971, the spread between the 10-year Treasury and 30-year mortgages has averaged 1.73 percent. One reason the spread is higher now is that the perception of risk is higher than normal. Personal credit delinquency and defaults are on the rise. The outlook for the global and U.S. economies is weaker.

While mortgage rates can certainly reverse course, at some point they will more closely follow the 10-year Treasury yield lower. Lenders will need to see the macroeconomic credit climate ease before that long-term interest rate premium eases. What buyers and sellers want to know is, when will that occur?

The Fed is Cutting: What Does that Mean for 2024?

What a central bank is trying to accomplish in setting monetary policy is neutral rate, one that neither stimulates nor restricts economic activity. Barring unforeseen circumstances, the end of the Fed’s rate cutting will almost certainly result in a higher neutral rate than what followed the past two cycles. In those cases, during the Great Recession in 2008-2009 and during the COVID-19 pandemic, Fed Funds went effectively to zero to stimulate the economy. Mortgage rates followed, falling to three percent (and lower) for an extended period. Prior to that, following the 2001 recession, 20-year mortgage rates fell from seven to five percent. That is the long-term average over dozens of business cycles, and roughly where we are heading over the next 12 months. Credit conditions may ease but mortgage rates are unlikely to fall much below five percent.

“Mortgage rates have already come down since [Federal Reserve Bank Chair] Powell’s remarks about three rate cuts in 2024. We have had customers locked at 7.25 percent and their rate is now 6.5 percent before closing,” says Mike Henry, senior vice president of residential lending for Dollar Bank. “The consensus is that rates will be lower in 2024 and stay lower.”

“As we enter a new year, much remains to be seen with how interest rates will change in 2024. There is a likelihood that mortgage rates could stay relatively flat in the early part of the year before potentially starting to fall as 2024 progresses. Declining rates could lead to an increase in refinancing, but that is not likely to be a wide-scale activity given the number of homeowners who have mortgages with rates in the four percent range or below,” says Joseph Cartellone, executive vice president, mortgage banking at First National Bank.

“Rates have already come down. We are seeing rates right now in the six and a quarter range in our market. That’s significantly better,” says Tom Hosack, president/CEO of Berkshire Hathaway Home Services The Preferred Realty. “With where we are you would think by the end of the first quarter, we would be under six, which should start freeing things up a little bit.”

“I think rates will be within a range of high five to six percent, but I don’t think there’s any exuberance that they will go much lower,” predicts Howard “Hoby” Hanna IV, chief executive officer of Howard Hanna Real Estate Services. “I think we have to be realistic about the expectations we put to consumers.”

Will a retreat to five percent long-term mortgages be enough to shift the trends in the housing market? There are a couple of metrics to watch for an indication.

For all the news coverage of rates and the unaffordability of housing for first-time buyers, the more damaging effect of the spike in rates has been the downturn in existing homes for sale. Homeowners with mortgage rates under five or four percent were reluctant to sell their homes when their new mortgage was going to be three percentage points higher. At the U.S. level, 85 percent of mortgages were below five percent in 2022, 39 percent were below four percent, and 23 percent were below three percent. By the end of 2023, the share below five percent fell to 80 percent. That is a five-point jump in those with mortgages above five percent, and that trend is accelerating.

The other long-term trend that reversed this year was the number of homes on the market. From 2011 to 2022, the inventory of homes for sale fell from 3.3 million to 700,000 before rebounding to 1.1 million recently. Perhaps the better reflection of the supply-demand imbalance is the number of months’ supply of homes for sale. The long-term average is six months’ supply of homes in the market at any one time. That metric ballooned to almost one year in 2011 but was at one month’s supply at the end of 2022 before rebounding to two month’s supply recently.

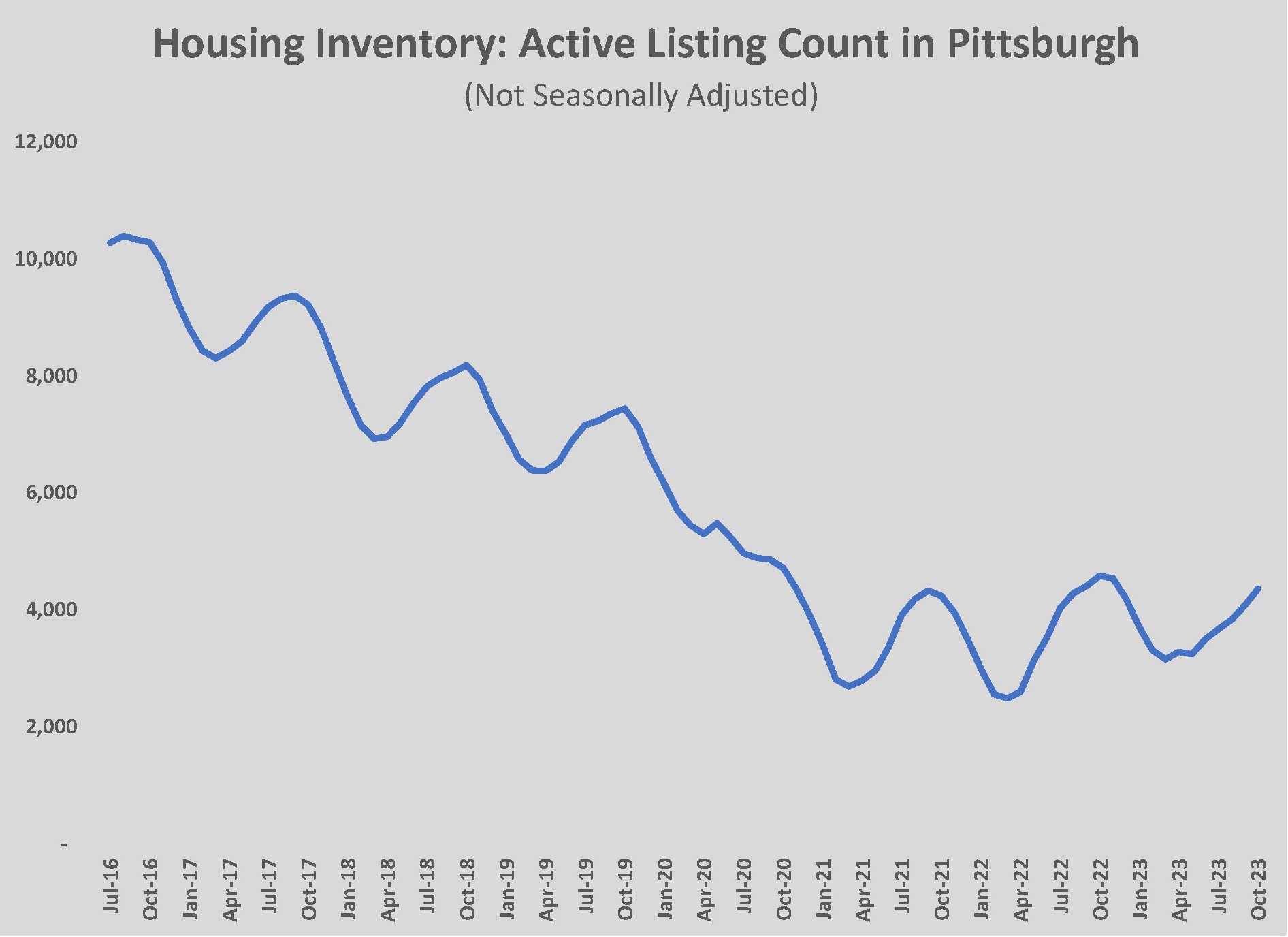

Pittsburgh’s housing market has followed the same market trends. From mid-2016 until spring 2022, the inventory of homes for sale plummeted from more than 10,000 to roughly 3,000. The inventory has recovered to more than 4,000 during the fourth quarter of 2023, but that is far short of what is needed to meet the demand.

It seems very likely that lower mortgage rates will move some homeowners who want to move up or downsize to sell. The gap in the inventory between 2016 and 2023 suggests that there is plenty of upside potential for existing homes to enter the market.

“There is still an inventory shortage. At the end of 2023, we had over 500 pre-approved mortgage applicants that had not purchased a home. That speaks to the lack of inventory,” Henry continues. Asked what mortgage rate would be low enough to thaw sellers, Henry says, “It has to be in the mid-fives. I think people would move from a three percent mortgage to a 5.5 percent mortgage to get the house they wanted.”

“Purchase money mortgage activity will be more dependent upon available housing inventory than interest rates, although with eventual lower rates, some homeowners may be willing to put their home on the market for their next move-up purchase. This could create opportunities for first-time homebuyers who have had very little housing stock from which to choose,” Cartellone notes.

Real estate professionals agree that the bigger problem with the housing market is still an inventory problem. Pent-up demand and supply are rooted in the pandemic and the difficulty of buying a home in such tight market conditions. That has created a seller’s market that has driven unusually high home prices.

“There are a lot of people out there who hate their house,” Hosack says. “They bought something during the pandemic and had to make multiple bids. Maybe they lost eight homes and won the ninth and aren’t happy with what they have.”

“The biggest challenge we still have in the market today, interest rates aside, has been the lack of inventory. I think lower rates will bring some normalcy to the market that will allow for increased inventory this spring. Sellers have been sitting on a lower interest rate and didn’t want to trade up at a higher interest rate that was seven or eight percent,” says Hanna. “We already have a significant buyer pool in play. There may have been some buyers take themselves out of the market because of higher rates, but we still saw a lot of buyer demand in 2023, just not enough inventory to supply that total demand. Lower rates bring more buyers to the market. That will maintain the market as a seller’s market. Rates will come down, but prices will still stay higher.”

Lower rates, even if just lower by a percentage point, should also bring an improvement to the buyer’s side of the table. That should help new construction as well as existing home sales.

“Traffic has remained solid. It’s the purchase decision that’s being extended for us,” says Paul Scarmazzi, CEO of Scarmazzi Homes. “Seventy percent of our customers are cash buyers. Nonetheless, I believe that if we get into the rate range of 5.5 percent or lower, it will have a significant impact on getting people off the sidelines and making purchase decisions.

“I don’t have an analytic way to quantify it, but I believe we would see a 20 percent increase in conversions (and therefore new builds/closings) in the coming year, which would add 15 or so homes for us.”

“We have two product lines that we build. On our quad line, which is half our business, half of the buyers are cash, and the others are low mortgage buyers, so the rate doesn’t impact the sales pace. On the single-family side, it will impact it. I would just be guessing but it should add five or ten percent. I don’t have a forecast for that, but I suspect it will be a surprise to the upside,” agrees Shaun Seydor, president of Pitell Homes.

There is some data to support Scarmazzi’s contention. Housing starts improved steadily year-over-year for most of 2023 in the U.S., ending the year with roughly 350,000 more single-family homes started, partly because of builder buy-downs. Builders have had to become more creative over the past two years to improve demand for new construction, especially those builders that appeal to a broader spectrum of buyers. One of the strategies that became widespread in 2023 was the practice of “buying down” mortgage rates. Lenders reduce the mortgage rate by 0.25 percent for each point (typically one percent of the purchase price) the builder contributes.

Seydor acknowledged that Pitell Homes purchased points to reduce customer mortgages as rates peaked.

“It was equating to a quarter point, sometimes a little more, maybe up to a half point. It depended on the loan and the customer,” he says.

“The home builders have been the smart guys. They realized that if they bought rates down to 5.9 percent, they could sell homes. Six percent seems to be the Rubicon that they needed to cross,” says Hosack.

Getting back to a mortgage environment below six percent, or lower, may seem like wishful thinking as 2024 begins. The fixed rate for a 30-year mortgage touched eight percent briefly as recently as the end of October, but conditions are supportive of long-term rates in the 5.5 percent neighborhood. Inflation, which drives mortgage rates higher, is easing. The December 22 report on core consumer inflation found that prices had declined by 0.1 percent from October to November. Moreover, long-term investors were also showing a certain amount of acceptance of lower yields. Long-term bonds, like the 10-year Treasury, were rallying and sending yields below 3.9 percent at year’s end, although a strong December jobs report bounced the rate back above four percent in early January. The lower trajectory is likely to resume as inflation continues to ease in the first quarter.

“If the 10-year Treasury gets to three percent, mortgages will be 5.5 percent. That would be another percentage point lower,” notes Henry. “Mortgage rates are tied to inflation, so if inflation returns to two percent, mortgage rates will be lower.”

Whether or not the decline in long-term rates is swift enough to bring 30-year mortgage rates to 5.5 percent by the end of 2024, it is clear that the run up in rates that began in spring 2022 has ended. There are factors that could accelerate the decline in rates but the catalyst for rapid decline would be an economy that is faring poorer than expected. That would not be a boon to the housing market, even if it meant lower mortgage rates and falling home prices.

The more likely scenario, which would bode well for the overall economy, is for incremental improvements in the housing conditions. Existing home sales edged up 0.8 percent in November, suggesting that some sellers were already responding to the easing of rates. Economists expect conventional mortgage rates to fall by another half percentage point by mid-2024, and then by less than one quarter percent the remainder of the year. Henry thinks a year of buyers and sellers seeing mortgages above five percent will help acclimate them to the fact that rates will be in that range for the long haul.

In short, expect 2024 to be a year of thawing for the residential mortgage market and the housing market in general. It is unlikely that rates, home prices, or the inventory of homes for sale will return to desirable levels in 2024. For the health of the U.S. economy, it is better that the housing market thaws gradually, rather than heating up again. NH