The housing market has become pretty exciting over the past few years, especially if you were lucky enough to be selling a house. One of the many reasons why the housing market has been interesting is that the mortgage market has been very boring. If the mortgage crisis of 2007 inspired the movie, The Big Short, the current market conditions could only spawn The Big Yawn.

Boring mortgage markets are good things for buyers, sellers, builders, real estate agents, and developers. All parties to a home sale or construction benefit from the certainty that comes with a boring mortgage market. Exciting or dynamic lending environments usually occur just before or after a remarkable (and usually bad) event. Even if the boring conditions are not the most favorable to one of the interested parties, the certainty of the market allows for each to prepare and react so that the deal closes successfully.

That is not to say that the housing market is not going through some dynamic times. Far too many buyers are trying to purchase a home compared to the number of homes being offered for sale. The unusual demand is occurring while a global pandemic is still raging, which is creating pressures on the supply chain and pushing prices significantly higher. The resultant inflation continues to be unpredictable and persistent. Still, lenders remain steady and certain. Even the variations in rate that have occurred in this turbulent time have been restrained. Mortgage rates have largely been within a half-percentage point range.

In 2022, as it was in 2021, the mortgage market will be influenced by two major questions: How high will interest rates go? And how high will housing prices go? The conditions that will determine the answers to those questions have become less predictable than before the COVID-19 pandemic, but the answer to both questions is likely to be not much higher.

Borrowing and Lending

A decade ago, the residential mortgage market was as turbulent as at any time in history. A global financial crisis just a few years earlier had drained liquidity from the market. Several million home loans were not going to get repaid, a reality that would reduce the earnings of banks and investors nationwide. In response to the financial crisis, U.S. government had created a new regulatory watchdog, the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau, and passed legislation – the Dodd-Frank Act – that put lenders on their heels. Home buyers and homebuilders faced uncertainty about whether or not loans would be approved.

Dodd-Frank was especially hard on banks and on the investors that buy residential mortgage-backed securities (MBS), which acquire the risk of roughly two-thirds of the mortgages that are originated in the U.S. That was especially true for the two government-sponsored enterprises (GSE) that provide liquidity and lending standards to the industry, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Regulation required higher levels of equity from buyers and more reserves against bad loans for lenders. That may seem like the banks’ problem but the downstream effect of raising reserve levels was to depress the amount of lending done. Fannie and Freddie, which effectively provide government backing to ensure against bad loans, were forced to tighten lending standards. That lowered loan-to-value ratios, added dramatically to the guarantees (and paperwork) borrowers were required to provide, and reduced the MBS volumes that Fannie and Freddie could purchase.

The impact on Fannie and Freddie is not widely understood by the public. Because of the implied government backing, the two GSEs allow lenders to shift the risk of default from their own portfolios to Fannie and Freddie. For that reason, the lending standards that Fannie and Freddie set are the ones adopted industry wide. Doing that provides certainty about what income requirements, down payments, appraisals, and other standards are acceptable for approving a home mortgage.

As the housing market healed throughout the 2010s, lending conditions eased. Banks got healthier. Reserve requirements were reduced (although the administrative burden for lenders was still inordinate). When demand for home buying surged again in 2015, the market was mostly normalized. With the election of a business-friendly administration in 2016, the stage was set for a return to pre-2009 conditions.

Prior to the 2020 election, there was growing speculation that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, would be removed from the federal receivership that each had been in since the GSEs imploded in fall 2008. The Trump administration favored fewer regulations on lending and was signaling an end to receivership – and the dissolution of the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau – in a second term. The election of Joe Biden cooled that speculation and the other headaches facing the Biden administration moved the privatization of the GSEs to the bottom of the agenda.

While the evolution of Fannie and Freddie out of government oversight may have meant looser standards for lenders and borrowers, the continuance of the status quo means that the mortgage industry has standards that are certain and consistent with recent years. During the last years of the Obama administration and the Trump administration, many of the regulations placed on lending in the aftermath of the financial crisis were eased. For 2022 at least, lenders will not see excess cash tied up in reserves and borrowers will not see a reduction in the leverage they can get for their down payments.

What is likely to be the key variable in the mortgage market from 2022 forward is the interest rate borrowers will be charged.

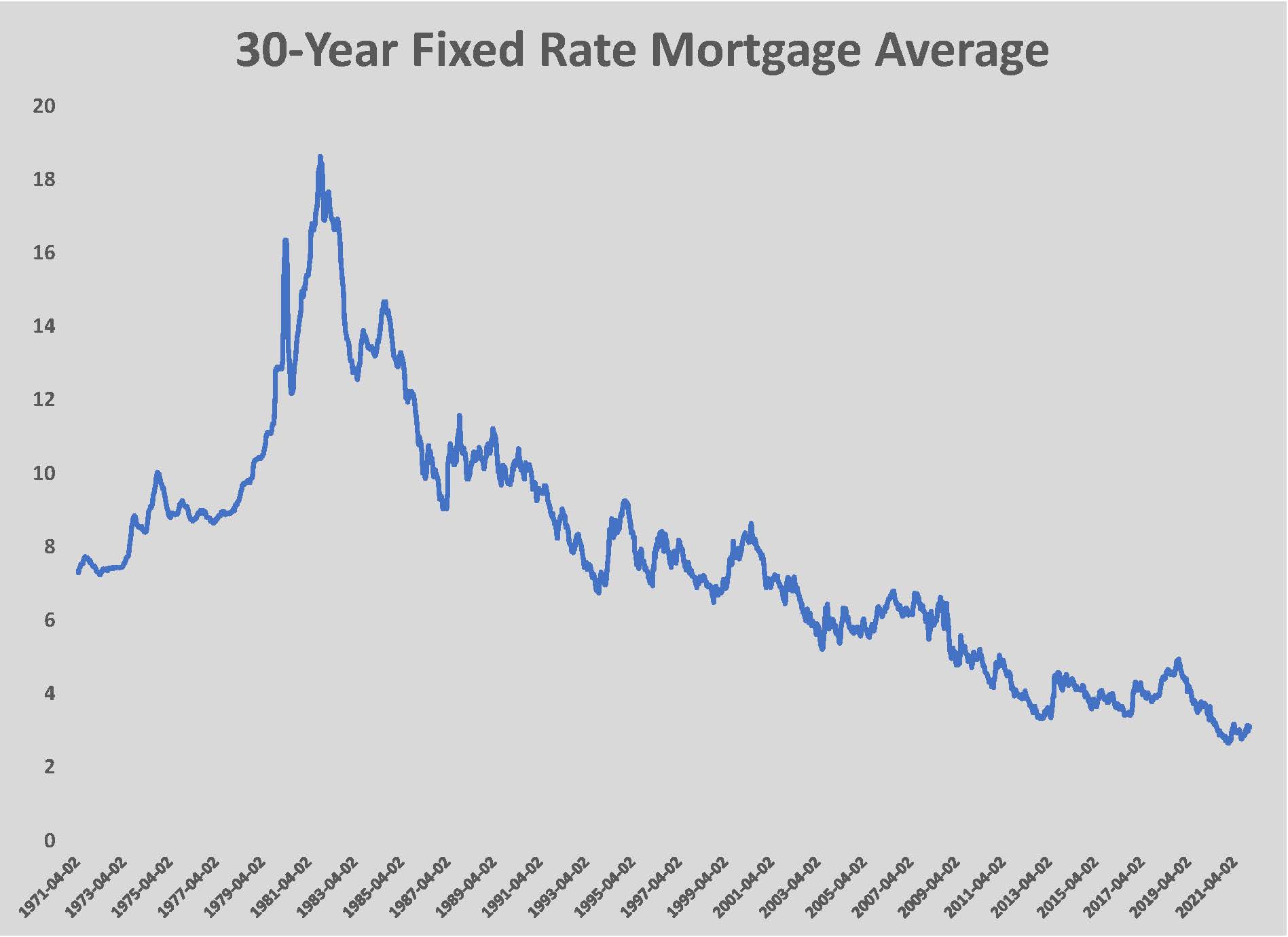

As it did in 2008 in response to the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve Bank cut its overnight bank-to-bank lending rate (the so-called Fed Funds rate) to 0.25 percent at the outset of the pandemic in March 2020. What has been different over the past two years compared to a decade before is the reaction of the bond and mortgage markets. Whereas 30-year fixed mortgage rates remained in the five percent range from 2009 through 2011, the same mortgage in spring 2020 carried a rate below three percent. Even over the past year, as inflation has grown to high single-digit levels, the interest rate on a fixed 30-year mortgage has increased only from 2.65 percent to 3.1 percent. That translates to a difference in monthly payment of $45 on a $200,000 loan.

While $45 is still real money in many households, that is not an amount that would be expected to have a chilling effect on housing demand. The data bears that out. Based upon home sales through November, it is estimated that there will be 7.1 million homes sold in the U.S. in 2021. That is a significant increase over the 6.5 million sold in 2020.

“When you look at the demographics, the Millennial generation and the generation after that, there are so many buyers and so many new households being formed because of the size of those population groups. I don’t think the rate increases that everyone is anticipating will slow or soften the market,” predicts Howard “Hoby” Hanna IV, president of Howard Hanna Real Estate Services. “Rates are so historically low that I think you’re going to have to see rates move to five percent or higher to create even a 60-day pause for buyers to get their heads around the idea that these are still very low interest rates.”

“Last year was one of the best years we ever had in our mortgage industry. People were working from home, and they were more aware of their bills and their interest rates, and they were talking to each other about it,” says Lisa Clore, senior vice president and director of mortgage lending at Community Bank. “But truthfully, interest rates at best may have gone to 2.75 percent and I think the average was 2.875 percent. Right now, we’re only at three and one-eighth percent and we’ve been back-and-forth between three percent and three and one-eighth.”

Clore notes that the flood of refinancing loans has slowed to a trickle in 2021. “There are a few stragglers but it’s usually because of a family situation or for home remodeling. Most people have already refinanced,” she says.

“Most of the people who can benefit from a refinance have done so already,” agrees Mike Henry, senior vice president of residential lending for Dollar Bank. “Refinancing is cycling down. There is some activity going on and usually there is a push when people start to see rates going up.”

Clore notes that the changing rates did nothing to slow demand for home sales. The same appears to be true for new construction, since new single-family permits were up roughly 12 percent over 2020.

“We haven’t seen any deals fall apart because of interest rate,” says Jeff Costa, founder of Costa Homebuilders.

“I think the Fed is behind the eight ball by not raising rates. My guess is that rates are going to rise,” predicts Paul Scarmazzi, CEO of Scarmazzi Homes. “But if rates rise even one full point it’s not going to turn off the spigot.”

Scarmazzi notes that if the central bank raises rates too much too quickly, it will be a shock to the system. He concedes that an aggressive response to inflation could be a wild card in the market but does not see that as a likely scenario. Instead, the steady pressure from demographics is likely to drive far more demand for sales than supply. That will keep demand for new construction strong even if, as expected, there are more homes on the market in 2022. There may be factors that will change that equation, but higher interest rates are not expected to be among them.

“Nothing has really changed. Our rates fluctuated up-and-down one-eighth of a percent but nothing dramatic. Often it moves up one week and back down the next,” observes Clore. “If you read one article, it sounds like rates are definitely going up. If you read another, they’re definitely going to be lower. We will have to wait and see what the Fed does.”

“If the Fed raises rates three times that could push mortgage rates up. We’re not feeling it yet and you would think a lot of these rates are cooked into the market. We’re still below three percent on a 30-year fixed mortgage,” says Henry.

Hanna sees little potential for impact on buyers from slightly higher rates, although he can imagine that the prospect of regular increases might affect sellers.

“There is still a lack of inventory in the market right now. The urgency factor is there. Could a slight interest rate tick make someone decide to move a little quicker? Possibly but I think people are moving as quickly as they can considering that we are still seeing multiple offer situations. I don’t think an uptick in rate creates a psychological urge to get off the fence,” he says. “One area I think interest rates could have an effect is on the supply side. We might begin to see sellers put their homes on the market if they think that this is the highest point of the market and if sellers think that an uptick in rates will reduce the number of buyers, that may make them more competitive in pricing.”

“One change that will affect buyers of more expensive homes is that Fannie Mae raised its conforming loan limit to $647,000 from $548,250. We were surprised by how much that increased,” says Henry.

Henry points out that the increase, which appears to have been an attempt to catch up with the rapidly rising home values, will have a big impact on mortgage underwriting and make borrowing less complicated. Loans that conform to Fannie Mae’s standards can be processed and underwritten automatically, using industry-wide technology that streamlines approvals for loans that fit inside the conforming definition. Loans for higher amounts are categorized as “jumbo” loans, which are subject to different underwriting standards and oversight. The new higher limit will keep more home sales in the conforming category.

“That’s a big deal. That level creeps into the jumbo loan market,” says Henry. “And we are seeing more jumbo loans than we have in some time.”

Buying and Building

One of the factors that is likely to slow down the new construction market, and the mortgage market, is persistent inflation. Although some of the effects of inflation are positive factors for housing – home values increase more rapidly during times of inflation – the overall impact of higher prices tends to reduce demand for homes. For most of 2021, the sources of higher prices have been somewhat limited to a handful of items, but the impact has been spreading and the outlook for when inflation will cycle down is uncertain. That has a lot to do with the causes of the current inflationary environment.

The unexpected uptick in consumer activity following the rollout of vaccines in spring 2021 created a perfect storm for manufacturers and suppliers, which were already dealing with decreased capacity from 2020. Capacity was decreased globally in 2020 because of the steep drop in demand during the shutdown period. When shutdowns eased in summer 2020, people began spending again, but almost exclusively on goods instead of services (like dining or travel). That shift in spending towards goods only moderated slightly once vaccines became readily available. Vaccines did not bring the full workforce back, however, so a stressed-out supply chain could not keep up with the heightened demand. This imbalance, which was further exaggerated by consumers with more cash in hand, improved by the end of 2021, but not enough to give a clear vision of when things would normalize.

The uncertain outlook could push some home buyers to the sidelines if they fear their incomes will not stretch as far. Inflation could also change mortgage standards, especially if rates rise unexpectedly. Conservative lenders may require higher income ratios for loan approval, since less of the borrower’s paycheck will be available for a monthly payment.

For homebuilders, the prospect of widespread inflation adds complication to a process that has already been hit by higher prices. One other odd and unexpected impact of the pandemic in 2020 was the increase in home remodeling and additions that occurred after people were stuck in their homes for an extended period. The boom in home projects caused spikes in lumber prices that spread to other basic materials and equipment. The residential building supply chain has yet to catch up.

“I think the market presents great uncertainty right now. Things are changing day-by-day,” says Scarmazzi. “The producer price index was almost 10 percent in mid-December. We’ve seen double-digit inflation numbers in our industry. If you think about the size of the building market as an economic engine in our country, continued inflation will be a problem.”

Inflation can also cause a headache for builders when the appraisals of the new homes are not keeping up with costs. Even in Pittsburgh, which has seen prices increase less dramatically than many major cities, appraisals lagged construction cost increases, which caused a few hiccups at closing time. Those seems to have been worked out during 2021.

“I’ve seen improvements in appraisals. We work with banks that really focus on new construction and I’ve seen the appraisals begin to keep track of what’s going on,” says Costa. “They are appraising what’s selling, but comparable sales are already underpriced to the market because prices are rising so fast. I feel lately that has been going more smoothly.”

“The challenges we see on new construction are supply and enough people to build the homes, but we saw minimal disruption with new construction,” Henry notes. “There was some, but it subsided pretty quickly as far as prices going up too fast or people not coming to work. It was not a significant number of loans that were impacted.”

Even if lenders are understanding how inflation is affecting new construction, housing affordability is a pervasive theme in politics and media. There are many angles to the story. Millennials entered the market later than their predecessors. Development costs rose too fast to continue building smaller houses profitably. There are racial and political overtones to the many narratives. The most likely answer to why new construction prices are so much higher is the simple one: supply has not kept up with demand.

America’s housing market has been out of whack since the housing bubble of the mid-2000s. The mortgage crisis precipitated an existing home inventory overhang of more than three million homes by 2010. In response, new construction dropped by two-thirds of the roughly 1.2-million-unit equilibrium for almost a decade. During that period, there was a coincidental shift in demographic behavior. Older Americans delayed leaving their family home to downsize. All these factors led to what is the status quo today, not enough homes to satisfy the demand of so many buyers. Whenever that imbalance happens, whether it is in the housing market or the peanut butter market, prices go higher faster.

Such imbalances have occurred in the housing market numerous times since the industrial era created the American middle class. Each time demand boomed ahead of supply, new construction boomed to catch up. For the most part, that reaction is missing in today’s market. Moreover, it is not just that new construction has lagged the demand for home ownership; affordable new construction has been virtually eliminated from most markets. In fact, the housing affordability “crisis” could be eliminated if the number of starter homes built today matched the number built just 40 years ago.

Freddie Mac published research in October on the housing supply. Called Housing Supply: A Growing Deficit, the research found that the housing market was 3.8 million units short of demand in 2021, an increase of 2.2 million units since 2018. The same study found that the lack of starter homes was the main driver of the shortfall. In 1980, starter homes – categorized as less than 1,400 square feet – comprised 40 percent of the new construction market. In 2020, the share fell to seven percent.

This trend is most pronounced in southern states, where nearly 50 percent of all new homes were starter homes in 1980 but ranged between 7.2 percent (Florida) and 15.9 percent (Kentucky) in 2020. Pennsylvania lagged only slightly behind the states with the largest decline in starter homes, with construction falling by 24 percent to 31 percent throughout the Commonwealth. The factors that contributed to making starter homes hard to build are definitely at play in Pittsburgh.

Costa Homebuilders is a custom builder that typically has 20-to-30 homes under construction during the year. Jeff Costa notes that rising costs and regulations make construction of the starter home of 40 years ago extremely difficult to do profitably.

“If we build a starter home, because of the quality materials we use, it would be $500,000. If somebody gave me the land for free – and lots aren’t free – we couldn’t build something that is a starter home for first-time buyers. Even the track builders are struggling to make that work,” Costa says. “One of the solutions is tiny homes but I’m not sure people want to live in a neighborhood full of tiny homes. It may not be what you want to hear but the answer in this climate is someone looking for a starter home should buy a condo.”

The difficulty in building starter homes at lower prices has an impact on the existing home market too. Younger buyers have been forced to shift their attention to smaller existing homes for sale, often resulting in bidding wars for homes that might otherwise attract few offers. The net effect of the lack of starter home new construction has been a marked reduction in the share of first-time buyers in the market. Last year, only 35 percent of mortgages originated were for first-time buyers, compared to the historic norm of 45 percent.

Hoby Hanna suggests that if the government regulators are going to tinker with lending rules, the goal should be to create more access to home ownership.

“On the underwriting side, there are discussions at the federal government level, looking at how to create affordable home ownership. If there’s discussion around those guidelines it should be to see if we are creating enough opportunities for homeownership among all Americans,” Hanna says. “I’m always wary when rules become less conforming because they are the back stop of the mortgage industry. The hope would be that the government would find a way to stimulate affordable housing stock that then is tied to the right mortgage product. It would help to create some stimulus to build new housing that creates more opportunities for homeownership.”

The factors impacting the construction market – higher costs, rising rates, and tight inventories – could be very disruptive to financing; however, the conditions are calm and steady as 2022 begins. That is a calming prospect for what is otherwise a dynamic and uncertain time. Scarmazzi notes how restauranteurs that adapted to the pandemic by adding outdoor seating have been thriving in 2021 and sees opportunities in the uncertainty. Certainty in the mortgage industry makes managing uncertainty in construction much easier.

“Uncertainty is never a good thing, but it doesn’t mean that you can’t find some light in it,” Scarmazzi says. “Underwriting is still solid, so I don’t think the mortgage market is going to be impacted like it was in 2007.”

Coming out of a period of low rates, which was also characterized by a surge of refinancing and home improvement projects, lending volume should be similar to that of 2021, which was down somewhat from 2020 levels. Banks obviously like to make more loans, but the volume in 2020 made for difficult circumstances to manage. Having a more predictable market pace makes it easier for lenders to assess risk and work with borrowers to optimize the conditions for a mortgage. That does not mean that inflation, or a negative turn in the COVID-19 pandemic, will not disrupt the marketplace, but conditions are more predictable now than the past few years.

“Would I like to see it be busier than what it is right now? I sure would. But would I like to see it be as busy as it was in 2020? No,” laughs Lisa Clore. “Last year we had people wanting to close or refinance on Christmas Eve. Nobody really wants to do that.” NH