The declining construction workforce has many causes, but the crux of the problem is that too few people have been attracted to the industry to sufficiently replace the older workers who are retiring in greater numbers.

Beginning long before the “Great Resignation” the construction industry has faced an increasingly difficult challenge in attracting workers. The declining construction workforce has many causes, but the crux of the problem is that too few people have been attracted to the industry to sufficiently replace the older workers who are retiring in greater numbers.

Construction is a rewarding, well-paid industry, but one that requires physical labor in all kinds of weather. The latter makes it less attractive to young people. And since at least the 1970s, American parents have increasingly guided their children away from blue collar work towards a college education. Perhaps three generations into a trend that views college as the route to a better career, advocates for construction work are swimming against the tide.

A shortage of skilled workers in construction makes it harder for home builders to complete projects as quickly. That is a business problem, but one that has downstream effects. The price of labor escalates faster when there are not enough workers. Projects that take longer also cost the builder more, a cost which is passed on to the homeowner.

`Over the next decade, this workforce shortage will worsen unless there are successful interventions to reverse the long-term trends. There are more Baby Boomer construction workers than any other generation, and they will have left the workforce by 2030. Technological advancements can take on some of the tasks that required workers to do but, for the most part, the construction worker shortfall will only be reduced by attracting more new workers. That is an effort that will take time and requires that we view construction as a career differently.

The Problem

Like many issues facing residential construction, the roots of the workforce shortage are demographic. Construction has been trending older for a generation, primarily because of the size of the Baby Boomer generation and the pressure those Boomers put on their children to find careers other than construction. As a result, the construction workforce has a demographic hole in the 25-to-54-year-old age cohorts.

To keep up with retirements, builders need to hire about 65,000 new workers each month, according to the National Association of Homebuilders (NAHB). In a labor market that is tight for nearly any position in all industries, increasing the recruiting to the construction industry has been challenging. In October, more than 400,000 construction positions were unfilled in the U.S. Roughly half of those were for residential construction.

As part of the Fall 2022 Home Builders Institute (HBI) Construction Labor Market Report, the estimated number of construction worker growth required to meet the demand for new homes is approximately 740,000. HBI also forecasts that from 2022 to 2024, the construction industry will need an additional 2.2 million hires to offset the pace of retiring workers.

This shortfall obviously affects the ability of homebuilders to meet their customers’ needs. It also limits their ability to expand to meet the potential demand from buyers who would otherwise build a new home because of the record low levels of existing homes for sale. New construction has historically been the solution for low inventory. Today, the shortage of workers limits the amount of new construction. That is another key factor in the affordability problem facing American homeowners. According to the Construction Labor Market Report, economists estimate the U.S. faces a shortage of homes for sale or rent of at least one million units, with a lack of construction labor a key limiting factor for improving both housing inventory and affordability.

There are other factors contributing to the shortage that date back to the housing bubble and the crash that followed in 2008. In hindsight, it appears that there were about three million more homes built than were needed to meet household formations during the mid-2000s. The crash that the overbuilding created meant huge job losses for residential construction workers.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that 60 percent of the construction workers who were laid off in the years that followed are no longer in the industry. The environment for new construction remained negative until the middle of the next decade, with builders nationwide only hitting the one million home mark again in 2020. That meant that demand for workers was suppressed for almost a decade, a market condition that made recruiting new workers more difficult.

In Western PA, where the median age is roughly 10 years older than the rest of the U.S., the demographic challenge is exaggerated. Compounding that heightened demographic disadvantage is a greater structural problem that Pittsburgh shares with other former industrial cities. Up until the 1980s, roughly 20 percent of the workers in Western PA were employed in manufacturing. They worked in plants that required daily maintenance and repairs, which created demand for workers with skills in plumbing, carpentry, electrical, concrete, ironworking, welding, and other construction trades. When most of those manufacturing facilities closed down within just a few years, the Pittsburgh region was left with an oversupply of workers. Many of these workers were forced to leave Western PA to find employment. For those who stayed, there was often insufficient demand for their skills.

Separate from the employment demand, a multigenerational shift was underway over the past 40 years that saw an ever-increasing share of high school students attend college. The U.S. economy underwent a shift from manufacturing to service industries, a structural change that accelerated as the U.S. led the boom in personal computing and information technology. This change created a need for tens of millions of additional white-collar workers. Parents, students, and guidance counselors responded, enrolling in colleges at higher rates. From 1970 to 1979, the number of enrolled students increased from 8.5 million to 11.5 million, as the population grew by 10 percent. By 2022, enrollment jumped to almost 21 million, an increase of 83 percent, while the population grew by 53 percent.

When society is pushing its future workforce away from blue-collar employment, the pipeline of skilled workers will decline. By 2020, it was clear that the demand for all blue-collar workers was on the rise, but the pipeline of workers was insufficient to meet that demand. Locally, this imbalance was particularly ill-timed. The demand for all types of construction has grown significantly over the past 20 years at a time when the pipeline of workers was at its lowest in Western PA. That is a headache for local homebuilders.

“There is a shortage and every year it seems to be getting worse. Ten years ago, we had multiple quality contractors to choose from, but more of them have moved on or gone out of business,” says Jeff Costa, president of Costa Homebuilders. “We are pretty selective about the specialty contractors we work with because of the quality of the custom home we build, but the problem is across the board.”

“It certainly has been an issue for some time,” agrees Chad Weaver, president of Weaver Homes. “We felt the crunch in 2021, beginning from when we were allowed to return to work from the pandemic through last year. We just don’t physically have the resources to cover the amount of work we have.”

“While Pittsburgh may have less favorable demographics than most other cities, the relatively small size of the new home construction market does lessen the downside from the workforce shortage”, notes Liam Brennan, vice president of Infinity Custom Homes.

“The labor shortage is affecting us but it’s not as bad here in Pittsburgh as in other markets,” Brennan says.

Even if the shortage is less severe in Pittsburgh, there are still tangible negative impacts on homebuilding.

“We have decided to build fewer homes rather than sacrifice the quality that is associated with our brand. If we can’t get enough qualified people, I won’t substitute workers that aren’t high-quality craftsman,” says Mark Heinauer, president of Barrington Homes. “Most of the crews of the subcontractors that work for us have been with us for 10 to 30 years. Almost without exception, those crews are 50 percent of what they were. We expect things to get better and we can gear back up when they do.”

Costa says that his firm has been able to keep up with demand, but that the schedules have been extended by several months. Weaver says his company jumped from 102 closings in 2020 to 146 closing in 2021 and could have built more than that except for the limitations of the workforce. He also points out that the losses are not limited to the homes that are not completed.

“With the people that are retiring it’s not just the resources, you also lose their knowledge, skill set and their work ethic,” Weaver says. “Even if you were to find a younger person willing to come into the trade, they won’t have the same production rate as the worker they replace.”

The Solution

The good news is that construction industry leaders recognized a decade ago that an extended uptick in construction demand would outstrip the supply of workers. The bad news is that there is no easy remedy.

“It’s very difficult to attract young people to the trades. If you look at the growth in the Mars-Cranberry-Adams area, the demographics, and the change in homes around here, there isn’t the blue-collar workforce to draw from locally,” explains Weaver. NAHB has a bunch of initiatives. BAMP [Builders Association of Metropolitan Pittsburgh] and the Pennsylvania Builders Association are trying, but it’s not easy work and it’s hard to attract young people.”

Reaching an equilibrium between the volume of work and the supply of workers can go one of two ways. Construction volume can decline or more workers can join the workforce. Given the positive impact of residential construction on the overall economy, the latter solution is far more desirable than the former. It is also the more difficult solution. If the market activity in 2022 is any indication, reducing the number of homes built may not be all that effective anyway.

According to the Census Bureau, residential activity plunged from the spring to the fall. New starts for privately-owned housing units declined by 21.1 percent, from 1.805 million units to 1.424 million units, between April and September 2022. The decline for single-family homes was steeper, with new construction falling 29.5 percent from February to September. In the six-county metropolitan Pittsburgh area, permits for new single-family homes also declined. Through October 31, 2022, permits for single-family homes were off by 19.9 percent compared to the same period last year, a decline of more than 500 homes.

Despite demand dropping by one new home in five, builders say the problem has not eased. That means homebuilders must manage the problem effectively if they are going to satisfy their customers and turn a profit.

Paul Spenthoff, president of Pulte Group’s division in Cleveland, notes that many of Pulte’s subcontractors changed their business model after the Great Recession to reduce the number of payroll employees. In the aftermath of that severe jolt to the housing market, many contractors now keep as many independent contractors employed as they do W-2 skilled workers. Spenthoff says that creates an opportunity for a stronger partnership between the homebuilder and its specialty subcontractors.

“We still have subcontractors that have been with us since we dug the very first hole in 1992.

At the beginning of the year, we sit down with our contractors and run our business plan out,” he explains. “We forecast extremely well. We are within two-to-five percent of our forecast every year. Most years it’s within one percent. Barring any economic changes that will disrupt the world we are pretty predictable and that allows our subs to have a predictable labor projection.”

“The second part [of our strategy] is to have a management meeting every Monday and use a slotting tool to program the release of homes according to the labor that’s available. We won’t put ourselves in the position of digging 30 basements when we only have 15 framing crews. That allows our vendors to staff with some accuracy,” Spenthoff continues. “Our pinch points in the past couple of years have been the supply chain disruptions. That’s been a bigger problem for us than our internal scheduling.”

“With our increased closings in 2021, we did everything we could think of to get subcontractors to add staff or to find new subcontractors to pick up the work,” says Weaver. “Typically, what happened was we had to resource overload our existing subcontractors. We have a scheduling program that allows us to look at each individual specialty contractor and their schedule, so it was easy for us to move those pieces around; but it turned into a chess game.”

Costa says that there has been a noticeable increase in the presence of workers from outside the Pittsburgh region. He specifically pointed to the use of Amish crews and more immigrants as a way to supplement the existing local workforce.

“The rays of hope are coming from the Amish community and having more immigrants than used to be here,” Costa says. “We are blessed to have more Amish construction workers near Pittsburgh than in other parts of the country. We now have immigrant workers in all trades. Compared to five years ago, it’s night and day different. We’re not still at the level of most other cities, but it is getting better year after year.”

Brennan says Infinity Custom Homes has learned to look at the workers hired by its subcontractors as though they are Infinity employees.

“We know we just have to treat talent like it’s talent. We need to make sure that our job sites are ready to be worked. We need to give the craft workers all the information and tools they need to be successful. If you do those things, and pay people appropriately, you can still find workers,” Brennan says. “But you have to check those boxes and be diligent as a builder to give them a desirable place to apply those talents. The same is true of management talent. We have to do those kinds of things to take care of our employees too.”

At nearly every level, the long-term solution being pursued is more robust attraction of workers. How that is being accomplished varies.

To mitigate the labor shortage, HBI has stressed the importance of appealing to middle school and high school students to help create a young, more diverse construction workforce and combat the aging trends at play in the industry. The institute says it is important for the industry to work closely with unions to train and place thousands more in the skilled trades. The HBI recently opened a BuildStrong Academy in Houston, which will provide tuition-free training to individuals interested in pursuing a career in the trades. The HBI operates similar academies in Denver, New Orleans, and Orlando, Florida. The HBI has pledged to open 15 additional academies by 2027.

NAHB has created numerous initiatives to attract workers from other industries, investing in skills training and recruitment for their members.

Those initiatives at the national level help to support the industry and can help raise awareness about the benefits of a career in construction. The heavy lifting of the effort is likely to be done at the local level, both by homebuilding professionals and school districts. For students who may not find college to be the right fit, construction needs to be elevated as a career option.

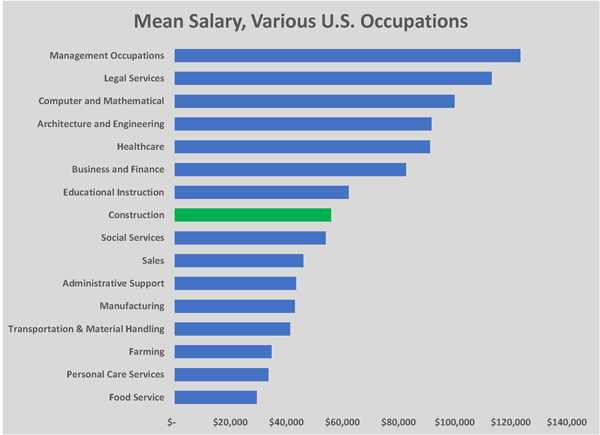

One measure that works in favor of construction is compensation. Construction wages compare favorably with the overall economy. The median payroll construction worker earns more than $49,000 annually, compared with the U.S. median wage of $45,760. That gap widens with experience and skill. The top 25 percent of workers in the construction industry earn $75,820 or more, while the top 25 percent in the overall economy earns at least $68,590.

There are also aspects of the construction process that make workers’ compensation more competitive than other professions. Subcontractors typically bid the cost of their services, including the cost of labor, from project to project. Since most skilled construction workers will be employed by subcontractors, their compensation can be bid higher when conditions are tighter.

“For 20 years, not enough people have been joining the construction trades and now that is coming home to roost,” says Steve Fink, president of Paragon Homes. “More workers are retiring. The cost of living has gone up significantly for those that are still working. Our subcontractors’ labor is priced from project to project and that labor has the ability to demand a 10 percent raise. That is a pipe dream for workers in other industries.”

What might work to close this huge gap in workforce need? Because of the skills required for construction work and the elevated safety concerns of the industry, it is more difficult to recruit workers from other industries; however, there are some industries that have workers that could adapt to construction more easily. Creating incentives for older workers to forestall retirement would slow the outmigration and reduce the shortage in 2024. In the final analysis, however, the most durable solution will be to bring in more new workers to the industry. That means having more success at recruiting high school graduates and women. In Western PA, the market would also be eased by increasing the number of immigrants in construction.

Women have been making up a growing share of the employment base since the Great Recession but were still only 11 percent of the workforce in 2021. That compares to a share of 44.6 percent in the total workforce (and 52.9 percent in managerial and professional positions). Women also have a smaller share of the manufacturing positions, at 30 percent, but that is nearly three times the share of women working in construction. Clearly, there is room for growth.

Immigrants to the U.S. have historically been drawn to construction because of the opportunities. In previous generations, when immigration was primarily from Europe, a worker with construction skills was more likely to find work and assimilate into American society. Those waves of immigration brought many of the workers who ultimately became entrepreneurs and construction business owners.

More of the immigration today is coming from Latin American countries and immigration policy has been a political issue that neither party has been willing to address. A clear immigration policy could be a boon to the construction industry. Immigrants comprise one-third of the construction workforce nationally. That share far exceeds the rate employed in construction in metropolitan Pittsburgh.

Builders in Pittsburgh could benefit immediately if an uptick in workforce participation from new immigrants or women occurred. The heightened emphasis on construction careers for students, however, is unlikely to bring immediate fruits, although that strategy may bring the best long-term returns. What is clear is that a slowdown in the number of homes built has been insufficient to allow the workforce to catch up. Perhaps a recession will slow residential construction another 15 or 20 percent over the next year and bring equilibrium to the supply and demand for labor. Even that level of decline may not be enough.

“We see the storm clouds forming for the economy but if we saw the right person, we would hire them today. And we would keep them on board, even during a recession if one should happen,” says Fink.

“Things are slowing down a bit right now giving everybody a chance to catch their breath, but the problem isn’t going away,” Weaver concludes. NH