On June 11, 2021, a group of 12 organizations who represent for profit and non-profit housing owners, operators, developers, lenders and property managers and cooperatives involved in both affordable and conventional rental housing, sent a letter commending President Joseph Biden for his action to ensure the viability of renters and landlords until the pandemic subsided. The letter also called for an early end to the moratorium on evictions for delinquent renters, asking that the ban be allowed to expire on June 30 as planned.

The coalition, which also included the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA), National Association of REALTORS® (NAR), and the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), noted that the strength of the economic recovery had rendered the assistance unnecessary. The call for ending the ban followed an early May decision by the DC Circuit Court of Appeals, which overruled a District Court for the District of Columbia ruling that the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) exceeded its authority in issuing the ban. Resolving the legal issue will require the Supreme Court to hear the case, but President Biden could render the dispute moot by executive order. That’s an outcome the real estate industry is supporting.

Landlords, who have seen rent collections fall by almost 10 percent since April 2020, are understandably anxious to be able to press tenants for payments with the threat of eviction in their pocket. While that may cause disruption to the apartment market for a spell, and some pain for those still struggling from the pandemic, the rental market has historically sorted itself out within six months or a year.

The fact that the premier organizations associated with home ownership, like the MBA, NAR, and NAHB, are supportive of the end to a foreclosure ban suggests that bankers, builders, and real estate agents are confident that the economy has recovered sufficiently to support home ownership.

In March 2020, when the novel coronavirus moved from Wuhan province in China throughout the rest of the world, very little was known about what would follow. It had been more than 100 years since the last true pandemic, and the global economy functioned very differently in 2020 than when the Spanish Flu circulated. That uncertainty led, wisely as it turns out, the Congress and federal agencies to push financial aid out to families in the U.S. Some of that aid was direct payments, but one key provision of the CARES Act of 2020 offered a lifeline to those financially impacted by the pandemic – a ban on evictions and foreclosures. As the pandemic unfolded, that ban was extended through 2020, and the Biden administration extended it further as part of the American Recovery Plan passed in early 2021.

The rapid pace of economic recovery suggests that the extension in the American Recovery Plan may have been longer than necessary. Still, agencies that aid those in financial distress are bracing for a surge in need once the ban is no more. There is no question that lifting the ban will cause pain for some number of Americans. The open questions are: how many will feel that pain, and will the pain be extended into the financial infrastructure that supports the housing market?

The Safety Net

Most people in the U.S. were reminded what a difference a day can make on March 13, 2020. The day before – mainly the evening before – the buzz about COVID-19 infections spreading around the U.S. turned into a chorus of cancellations that seemed unthinkable to most. The NBA, NHL, Formula 1, and the NCAA Basketball Tournaments were among the first dominoes to fall in response to outbreaks of positive tests among the teams. Throughout that night, governors and school districts around the country started closing public facilities. By Friday, the 13th, most of the country was being prepared to shut down and stay at home after the weekend.

We had a month’s warning this might occur, of course. Outbreaks in China, then Italy and Spain, led to lockdowns of those countries that were on the news for weeks before the first cases showed up in the state of Washington in March. But there was a bit of “that can’t happen here” feeling in America up until professional sports starting cancelling seasons. Even during the following week or two, the feeling persisted that we could stay at home for a few weeks or a month and then we would get the “all clear” signal. That proved to be wishful thinking.

By the end of March, when it was obvious that normal activities would be ceased for months or more, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security Act of 2020 to be a bridge for those who were most directly impacted by the cessation of normal life. Roughly 20 percent of the country became unemployed within the following 60 days. One of the key measures in the CARES Act was the prohibition against evictions and foreclosures for 120 days, which was eventually extended by the Biden administration through the end of June.

At the time the CARES Act was passed, the federal agencies that hold most mortgages, including Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, VA, FHA, and USDA, issued rules that gave borrowers the opportunity to put their mortgage payments into forbearance for a year or longer with extensions that were permitted.

For the millions of homeowners who were unexpectedly out of work, these two steps provided a safety net that would allow them to stay in their homes, even if they could not make payments. In addition to providing security for homeowners, the ban on foreclosures and forbearance kept the multi-trillion dollar mortgage industry from facing an onslaught of loan defaults. Of course, the government intervention didn’t alter the underlying financial insecurity – or stability – of the U.S. homeowner who was negatively affected by the pandemic. As the ban approaches its sunset and the window closes on extended forbearance, lenders are soon to find out how insecure or stable the finances of the homeowner are.

Experts are more optimistic that a wave of foreclosures is not building like they were just a few months ago.

Vaccines, and the speed with which U.S. citizens have been getting vaccinated, have proven to be as effective at boosting the economy as they have at bringing COVID-19 under control. Gross domestic product (GDP) is growing at rates unseen in 75 years. Demand for goods and services is roaring back and employment is expected to follow. The fly in the economic ointment thus far has been the impact of government intervention, which seems to be acting as an incentive for many workers to remain out of the workforce. Those extended unemployment benefits end on September 30, after which the size of the U.S. labor force is expected to return to pre-pandemic levels.

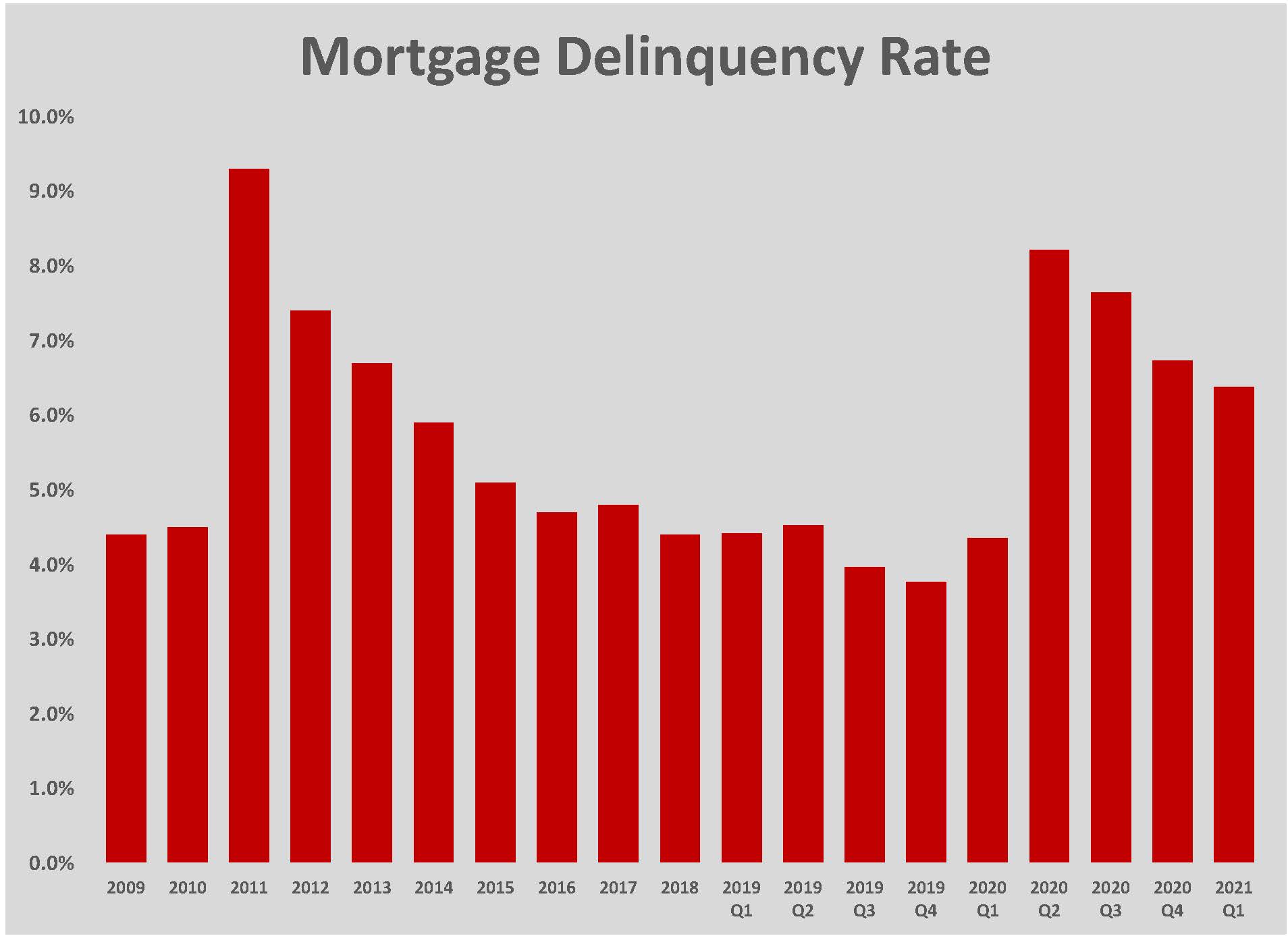

As unemployment falls a bit lower each month, the outlook brightens for the mortgage market. The pace of recovery thus far has made a big impact on how well borrowers were keeping up with their payments. From a high of 8.22 percent of mortgages that were delinquent at least 30 days in June 2020, the number of borrowers behind on their payments fell to 6.38 percent at the end of the first quarter of this year. Even more promising was the fact that those 90 days delinquent comprised only 4.25 percent of mortgages, although the share of those 90 days delinquent rose .07 points from the end of 2020.

Similar improvements have occurred in the share of mortgages in forbearance. From a low of 3.74 percent in March 2020, the share of loans in forbearance jumped to 5.95 percent in April 2020 and peaked at 8.55 percent during the week of June 7, 2020. One year later, only 4.04 percent of loans were in forbearance. That still represents more than two million mortgages, but the MBA expects 1.7 million borrowers to leave forbearance by September.

It is important not to conflate forbearance and delinquency. Although their respective share of mortgages is similar, many loans in forbearance were not delinquent prior to getting the reprieve from payments. Mike Henry, senior vice president of residential lending for Dollar Bank, notes that especially during the early months of the pandemic, borrowers opted for forbearance out of an abundance of caution, not necessity.

“Many people went to forbearance who didn’t need to go to forbearance but did so because they could. They didn’t know what was going to happen and neither did we,” admits Henry. “Where it hurt customers was in financing the amount that they had in arrears. The Fannie Mae rule is that if you are in forbearance, you are not eligible to refinance. You can take yourself out of forbearance and then you can refinance, but you can’t pay off the amount that you deferred by adding it to the balance of the loan. To do that you must make three consecutive mortgage payments. You can’t pay off all three at once; you have to demonstrate that you could make three payments in a row. That’s caused frustration for some of our customers who had to wait to refinance their mortgage.”

That frustration is likely to heighten as two million borrowers exit forbearance nationally between now and the fall. Neither lenders nor borrowers understood the rules when the situation changed last spring, mostly because the rules weren’t in place. Compounding the uncertainty at the time was the fact that some of the agencies, especially Fannie Mae and FHA, promoted the concept that the missed payments could be tacked onto the end of the mortgage. While that is true, as Henry explained, there is little flexibility in the steps to take out of forbearance.

The benefits of the CARES Act, the employee retention that the Paycheck Protection Program facilitated, and the rapid improvement in the economy all combined to ease the economic pain that seemed inevitable when COVID-19 shut down the country. Millions of Americans weren’t able to avoid the pain of lost jobs and economic uncertainty. Even as the virus recedes in the U.S., there are fewer restaurants and stores open today than in winter 2020. There will be pain inflicted that neither eviction bans, nor loan forbearance can deflect.

“The end of the mandated forbearance doesn’t mean we won’t need more forbearance. It will depend on the situations,” says Henry. “What I don’t know is how many customers that we have in forbearance won’t be able to manage their payments once they are removed from forbearance. I’m sure there’s a segment of our customers who haven’t recovered but I don’t know how much of that there is.”

Even the most optimistic forecasters expect unemployment to linger above pre-pandemic levels until early 2022. More likely, it will be until 2023 before everyone who had a job at the beginning of 2020 is employed again. That means there will be borrowers who cannot make ends meet and tenants who can’t pay their rent. The way forward will be bumpy for many renters and homeowners, but the character of the recovery may allow lenders and landlords to show patience that will prevent the kind of damage to the housing market that was experienced from 2008 until 2012.

Asked whether forbearance was a prelude to future payment problems, Lisa Clore, senior vice president and director of mortgage lending at Community Bank, noted that the bank’s portfolio was not seeing trouble.

“We did some forbearance for our customers, but have we had any repercussions from them? No, not that I’m aware of,” Clore says.

Landlords have seen rental income decline but the share of renters making payments has increased year-over-year, according to the National Multi-family Housing Council (NHMC). Since the latter part of 2020, the number of renters making payments each month has increased from roughly 93 percent to 95 percent. That compares to around 97 percent prior to the pandemic. For national apartment owners that has meant lower income and profits, but the pain of the pandemic has been more pronounced for the “mom-and-pop” landlord. Half of the 49 million rental units, and two-thirds of the 22.5 million rental properties, are owned by individuals. The moratorium on evictions has left these landlords with little recourse for dealing with tenants who can’t – or won’t – pay the rent. But the NMHC notes that the moratorium does not eliminate the obligation of the tenant to pay rent; patient landlords stand the best chance of getting whole when the dust settles.

The mortgage industry bears little resemblance to the apartment market. There are no “mom-and-pop” lenders, and the business of lending money is highly regulated. Nonetheless, lenders expect to be paid back when they approve a mortgage. If homeowners are allowed to defer payments for a year or so, or are protected from foreclosure, that expectation of repayment doesn’t change. When the ban on foreclosures expires at the end of June, assuming there is no further extension, there will be a period of adjustment as distressed borrowers try to work through economic stress.

Thus far, there have been no comparisons drawn to the mortgage crisis that unfolded from 2007 through 2009. Lenders have plenty of liquidity and the number of borrowers experiencing distress is one-third what it was in 2008. The housing market has strengthened since the pandemic began, which is good news for those who will be unable to make their mortgage payments in July.

Since June 2020, the average increase in equity for a U.S. homeowner was 16.2 percent. That translates to an increase of $26,000 per home, a stark contrast to the conditions in 2009, when homeowners in many states saw the value of their homes decline by 40 percent. Increased equity opens the door for refinancing and offers homeowners who cannot make ends meet the option of selling their home and walking away with cash in their pockets.

Selling ahead of foreclosure is not the ideal ending for a residential mortgage. Sadly, the economic pain of COVID-19 will force many to move from home ownership to renting. At this point, however, the pandemic does not appear to be causing the kinds of systemic damage that followed the mortgage crisis in 2008.

For the mortgage market that means there will not be the kinds of regulatory deluge that followed the financial crisis. That crisis precipitated the Dodd Frank Act and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), both of which placed regulatory burdens on lenders that ultimately had the unintended consequence of making it harder to get a mortgage and develop residential communities. In 2008, the banking industry needed tougher regulations on lending standards that had become dangerously loose. In contrast, lenders proactively tightened their standards in 2020, exercising more care in the face of massive unemployment and economic uncertainty. Now that the uncertainty has faded, banks have returned to lending conditions that were in place before COVID-19. For the most part, those conditions reflect a mortgage market that is healthy and accommodative to lending money, but with the kinds of standards that reflect the expectation of repayment.

“We tightened up standards a little bit but not because we’re anticipating problems,” Clore says.

“We went through tightening some underwriting guidelines last year. Fannie Mae still has some rules in place but that’s more about documentation than credit standards,” says Henry. “As far as product restrictions or loan-to-value ratios, we have gotten back to pre-pandemic standards.”

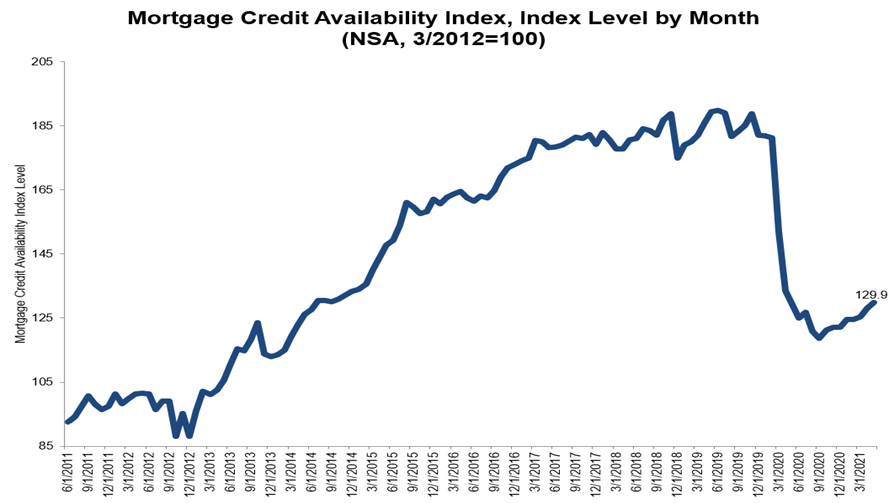

The MBA’s Mortgage Credit Availability Index (MCAI) is a good reflection of how the lenders are behaving. An analysis of various borrower credit data like loan-to-value, credit score, and loan type, MCAI falls when lenders tighten standards, and vice versa. In May 2021, MCAI rose to 129.9 (with March 2012 equal to 100), the sixth consecutive month without a decline. After peaking at 185 in December 2019, MCAI plunged last March and bottomed out at 120 in August 2020. The steadily rising index since then indicates that lenders are relaxing the tighter standards and borrowers are meeting the standards. That is what would be expected in an economic recovery.

For all the optimism felt about the U.S. economy as summer 2021 begins, the threats to a robust recovery remain. Too many people remain unvaccinated, despite an abundance of vaccines. A battered supply chain is providing a drag on sales and growth, both for consumer goods and businesses trying to invest. Much of the world is unvaccinated, including the majority of the population in industrialized countries like Japan, South Korea, Australia, and parts of the European Union. That represents a threat of COVID variants that could avoid vaccines and return the U.S. to pandemic-level infections. And until unemployment levels fall below four percent again in the U.S., there will be an elevated chance of mortgage defaults and missed rent payments. Based upon what they are seeing, lenders are remaining vigilant but confident that problems will be limited.

“As far as Dollar Bank’s portfolio goes, we are not worried about it. There could be some slightly elevated credit issues, but they would be slightly above normal,” says Henry. “As for the overall market, I don’t see anything that suggests there will be an overwhelming number of foreclosures or anything of that nature.”

Those with long memories may recall that lenders were similarly unconcerned about the impact of sub-prime mortgages in 2007. In the case of the housing market in 2021, however, there don’t seem to be the kinds of amplifying factors – like Wall Street issuing bonds backed by sub-prime mortgages – that spun the mortgage market into crisis in 2008. Moreover, those charged with regulating and supporting the banking system, like the Federal Reserve Bank, are watching the situation closely. That wasn’t the case during the housing bubble.

“I’m not terribly concerned about it either. You should always be circumspect when bankers say their credit quality is pristine but in the current circumstance it really is,” jokes Mekael Teshome, vice president and senior regional officer of the Pittsburgh Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. “We are hearing across-the-board that borrowers have come out of forbearance and they’re making payments now. Cash balances are up, and delinquencies have fallen to low levels, so I’m with the bankers. I am not seeing anything to cause worry about a bigger problem.” NH