The financial crisis threatened to ruin banking a decade ago. Many banks did not survive. Those that did had to radically alter their businesses as an era of historically low interest rates and dramatically higher regulation set in. Popular negative sentiment about banking allowed reforming politicians to push through the Dodd Frank Act, which included the establishment of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). In addition to the strains from regulatory pressures, banks had to adjust to CFPB rules that eliminated or cut many fees that boosted profitability.

Economic recovery was the remedy. With fewer competitors, and low rates driving refinancing, loan volumes and margins returned.

Today, the global economy has slowed to a crawl. Even in the U.S., gross domestic product (GDP) fell to two percent in the third quarter. Banking is coming into the late phase of the business cycle and there are numerous signs that business will be tougher in 2020 and 2021 than in recent years. Loan volume has peaked. Top line revenues are flat. The yield curve has bounced back into positive territory following three rate cuts by the Federal Reserve Bank but the relationship between long-term and short-term rates is still flat, leaving banks little spread.

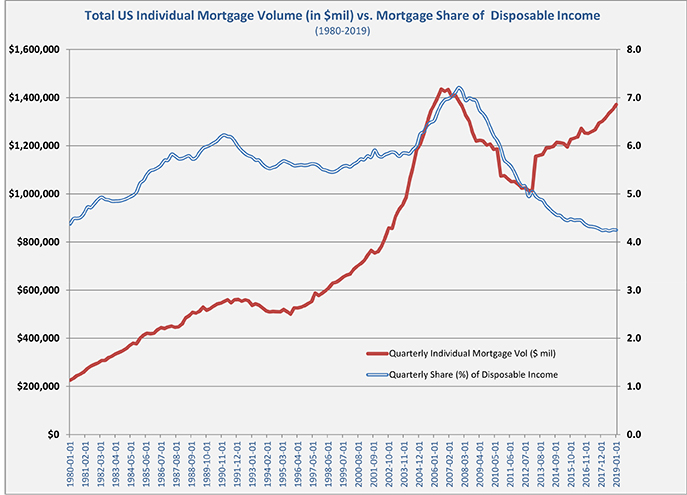

There is an upside to the low interest rate environment for the banking industry and that is the boost it is giving to mortgage borrowers. Whether the low cost of borrowing allows homeowners to buy more house or to push renters to become buyers, the end result is a boost for bankers that was unexpected one year ago. And if Baby Boomers start selling their houses, it’s a boost that might spark another housing boom.

The Low Rate Environment

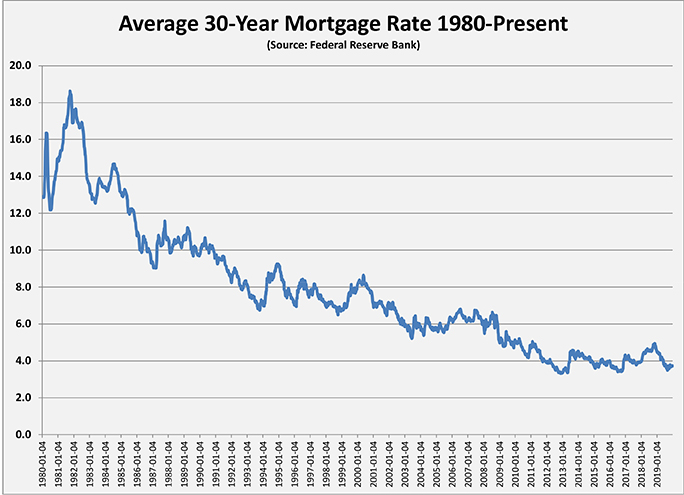

In December 2015, the Federal Reserve Bank hiked its overnight borrowing rate by one-quarter percent for the first time since the financial crisis of 2008. Central banks the world over had reduced rates as part of efforts to stimulate the battered economy into recovery. The rebound was slower and lower than expected, but by the end of 2015, the Fed saw reason enough to begin normalizing interest rates from near zero percent. During the next three years, the Fed made another five quarter-point hikes and mortgage rates began to edge up. Last December, however, the Fed went one hike too far.

Citing a healthy economy, the Federal Reserve pushed the Fed Funds rate for the fourth time on December 20, 2018, to 2.25-to-2.5 percent. Rates had been raised a total of five times in the previous three years and many observers felt that the Open Markets Committee (FOMC) would pause in the final meeting of 2018. Markets began to falter ahead of the FOMC meeting and the stock market plummeted 16 percent by Christmas. The decline accelerated fears of a looming recession.

In reaction to the market response, the Federal Reserve Bank took another look at the economy in winter 2019, leaning more on its dual mandates of full employment and low inflation. Over the next nine months rates were cut three times, leaving the Fed Funds rate at 1.5 percent as 2019 ended.

Part of what motivated the central bank was the desire to return to more normal rates, but it was clear that the markets, especially the bond markets, weren’t on board. Throughout the past few years, investors have been buoyed by the low inflation rate, which keeps interest rates down on longer-term debt. A significant chunk of that long-term debt is mortgage-backed securities (RMBS), the financial product that is a bundle of thousands of home mortgages. These RMBS investments allow banks to make loans and then sell them to large investors looking for more secure, long-term income. Those investors, which are often large pension funds or Wall Street firms, expect to collect interest that is commensurate with the risk of the investment. The risks are primarily the chance that homeowners will default on the loans and the chance that inflation will be higher in years to come.

U.S. homeowners generally repay their mortgages so the factor that has driven the interest rate on long-term mortgages has been the risk of inflation. Because the rate of inflation has been stuck at two percent or lower for a decade, investors haven’t been demanding much of a premium for long-term investments, whether that is 10-year Treasury bonds or 30-year home mortgages.

That’s a long and technical explanation for what is pretty obvious to the average home buyer. Interest rates are low.

The Fed’s decision to raise rates more aggressively did impact home mortgages, as has the decision to cut them in 2019. In fact, rates had climbed above four percent at the start of 2019, and most bankers were expecting the upward trend to continue.

Twelve months later mortgage interest has retreated to record low territory.

Interest on 15-year mortgages dipped well below three percent, quoted at 2.7 percent on December 19. The rate for the more popular 30-year fixed mortgage was 3.7 percent on that date. That’s a full point lower than the rate 12 months earlier. That’s close to the lowest interest rate on a 30-year fixed mortgage over the past decade. In fact, 30-year mortgage rates were at or above five percent during the economic crisis of 2008-2009; and, rates were above six percent at the height of the housing bubble.

How has this latest dip in interest rates impacted the housing market?

“The lower rates last year

were phenomenal for Community Bank. We had a record breaking year,” says Lisa Clore, senior vice president & director of mortgage lending at Community Bank.

“It seems like 2020 is going to start out the same way. There

are a lot of loans in the pipeline and people are still calling.

It’s not just purchase loans.

It’s new construction loans

and refinancing.”

“We have definitely seen an increase in refinance activity since late spring or early summer when rates began to come down, which we were not anticipating,” says Mike Henry, senior vice president of residential lending at Dollar Bank. “We expected that rates would remain in the four percent range and maybe tick up to five percent. We are significantly ahead of our anticipated mortgage originations for 2019.”

Dollar Bank’s experience is not an outlier. According to the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA), the low rates pushed loan volumes to levels unseen since the Federal Reserve cut rates nearly to zero 12 years ago. The total residential loan volume exceeded $2 trillion in 2019. Of that, almost $1.3 trillion went to home purchases, with another $800 billion tied to refinancing existing mortgages. Dollar Bank is an active new construction lender, with ten percent of its mortgages from new construction. Because prices for new construction and existing home purchases run about 50 percent higher than refinancing, Dollar’s origination volume tends to skew towards purchases.

“We’re still seeing purchase activity. During the first quarter of the year it was probably 70 percent purchase and 30 percent refinance. Now it’s about 50-50,” says Henry. “It definitely increased loan production.”

Community Bank saw its loan demand spread evenly across loan types. “Roughly 30 percent of our loans were new construction and 40 percent were purchases. The other 30 percent were refinances because that just kicked in during the last quarter,” says Clore.

“On the purchase side it has created more affordability for people, so people are able to purchase more than they were a year ago,” says F. Duffy Hanna, president of Howard Hanna Financial Services. “That’s good for sellers and buyers. We’re a purchase mortgage money business so we don’t do much refinance. Last year we had none, so the drop in rates definitely helped that side of the business.”

Impact on First-Time Buyers

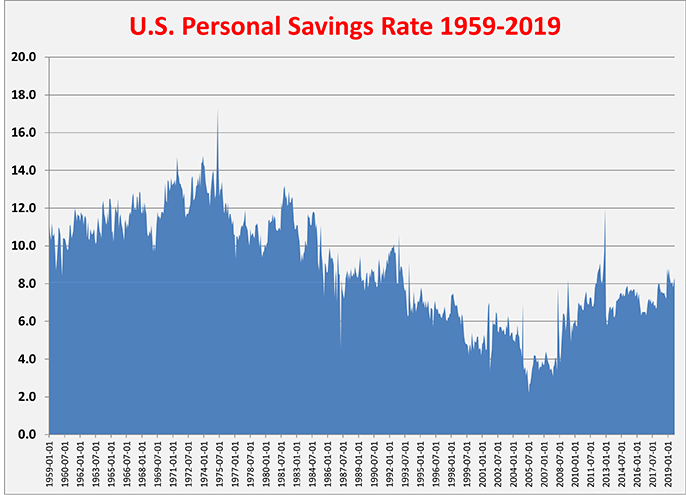

The Great Recession left several scars on the housing market. One of them was the chilling effect it had on young adults, the so-called Millennial generation. The largest, and arguably best-educated, generation ever born in America, Millennials were coming of age as the housing bubble burst and millions of people lost their homes. Those traumatic events played out in bold headlines, in real time, as Millennial adults were beginning their working careers. In the way that the Great Depression made the Silent Generation financially conservative, the housing crisis made Millennials wary of many of the commonly accepted beliefs about the value of owning a home.

High college debt and high unemployment added practical obstacles to the emotional worries, suppressing the transition from renters to homeowners for young adults.

A decade of economic growth has made those obstacles less imposing and the decline in interest rates has been a boon to the home ownership activity among Millennials and other first-time buyers.

Ellie Mae, the mortgage application/processing technology company that manages the Uniform Residential Loan Application used by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, published a report on the mortgage market activity in late 2019. Ellie Mae’s report echoed the observations about the increase in refinancing and made note of several important trends related to

young homeowners.

The report showed 34 percent of all loans closed by Millennials through the third quarter of 2019 were refinances. That’s the highest share since Ellie Mae began tracking in January 2016. Breaking it down by loan type, refinances made up 41 percent of conventional loans closed by Millennials, up slightly from 40 percent in September, and the refinance share for FHA loans remained flat at 10 percent. For VA loans, the refinance share dropped to 42 percent.

This increase in refinancing activity, which the decline in rates enabled, puts Millennial homeowners in better fiscal condition. With poorer balance sheets than their older neighbors, Millennial homeowners more frequently borrowed at higher rates than the market’s best and more frequently paid premium mortgage insurance (PMI). The refinancing of mortgages from

the previous 12-to-18-month period allowed many Millennials to avoid PMI or shorten the term of their mortgage from 30 years

to 15 years. A big chunk of America’s homeowners now pays less each month, or are building equity quicker, which will be a catalyst for the move-up market going forward.

Joe Tyrrell, Ellie Mae’s chief operating officer, remarked that lenders should take advantage of the rate environment to market more aggressively to first-time buyers. He points out that a greater share of these buyers has not entered the home buying market and are unfamiliar with how affordable residential mortgages have become.

Millennials appear to be getting that word. Home ownership rates plummeted to 62.9 percent in the decade following the housing bubble, but that trend began reversing in fall of 2016. The rate of home ownership now sits at nearly 65 percent, close to the historical norms. The reason for the rebound is the increase in home ownership among the Millennial generation. This is especially true among the leading edge of the generation. Home ownership among those between 35 and 44 years old jumped to 62 percent in 2019; and the rate among those between 18 and 34 years old grew to 37 percent. With the largest share of Millennials just hitting 30 years old, the level of home ownership should really tick higher in the next few years.

“Everyone was saying five years ago that the Millennials would never buy homes, but there are more young people out there buying homes right now,” says Duffy Hanna.

If the accelerating rate of home ownership among Millennials continues to be the trend, however, the increased demand will exaggerate the biggest problem facing the housing market: low inventory.

The subprime mortgage crisis created a wave of foreclosures unlike any since the Great Depression. Observers worried that this overhang of foreclosed homes, which was estimated to be 7.8 million houses, would keep prices depressed and volumes low for years. While the high rate of foreclosures damaged the market, the inventory of homes for sale was steadily consumed. By the mid-2010s the problem became a lack of inventory, rather than an overhang of foreclosed homes.

Concerns about excess inventory overlooked an emerging demographic trend. Estimates of the number of homes for sale didn’t account for the shift in how older homeowners were behaving. As Baby Boomers became empty nesters, there was an increase in demand for low-maintenance living options. This drove construction of attached homes and multi-family communities geared to seniors; however, the improvements in healthcare in one generation meant that fewer empty nesters were leaving their homes than expected. Baby Boomers were choosing to age

in place.

This trend of aging in place had a bigger impact – as could be expected – in markets with an older population. Pittsburgh is one of those markets. Although the median age of a resident of the City of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County has declined significantly, Metropolitan Pittsburgh has a larger than average share of homeowners over the age of 65. That fact is showing up in the home sales data.

Existing homes sold in 2019 fell again for the fourth consecutive year, although the total number of units sold – including new construction – was up 3.2 percent. Total listings were off by 10.17 percent, a surprise considering the uptick in Pittsburgh’s economy. Not surprising was the five

percent jump in average sales price to $199,821.

“In our region, the residential real estate market remains stable,” says Tom Hosack, current president of West Penn Multi-List, and president and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway Home Services The Preferred Realty. “Houses are selling, but we aren’t seeing the supply being replenished as

quickly as houses are moving off the market.”

Mike Henry says that real estate agents are still giving him

feedback that the low inventory

is driving competition for homes on the market, which in turn

is discouraging some first-

time buyers.

“People were still getting into bidding wars on houses,” Henry says. “Many of the first-time buyers just decided to sign a one-year lease and wait it out another year.”

New construction is also low. Lot development slowed in Pittsburgh just ahead of the Great Recession and conditions for residential development have been poor since then. Since the downturn, there have been about 2,800 new single-family homes built annually, compared to around 4,000 per year prior to then. Over the last 15 years, the number of townhouses and other attached homes steadily increased, as Baby Boomers downsized; however, even that trend has reversed since 2017 because of anemic

new development.

The backbone of Pittsburgh’s economy is healthcare, education, and emerging technology. The region is attracting younger people at a higher rate than most other cities. These new residents are, for the most part, better paid than that average Western Pennsylvanian. In a time of record low borrowing costs, sales to first-time buyers in Pittsburgh should be skyrocketing but that isn’t the case. In Pittsburgh, at least, it is inventory that is influencing the market, not rates.

The Outlook

The Federal Reserve Bank voted December 18 to hold the federal funds rate in its target range of 1.5 percent and 1.75 percent. In its final meeting of the year the FOMC signaled that it expects to hold rates steady in 2020, showing that it is comfortable waiting to see how the U.S. economy fares before acting again. Its behavior during 2019 was an attempt to cushion the economy against the U.S.-China trade war and slowing global and domestic growth.

Gus Faucher, chief economist for PNC Financial Services Group, believes the Fed will stay the course at the current rate levels in 2020. He sees the market for yield-producing debt – like residential mortgages – being equally stable. Faucher forecasts the 30-year mortgage rate to be more or less at the 3.7 percent it currently yields.

“I do expect that we will see fixed mortgage rates staying around that level through most of 2020,” Faucher says. “Inflation expectations remain low. Economic growth is going to be a little softer, so I don’t expect to see much movement up or down in mortgage rates over the course of the year.”

Economists at Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae agree. In its fall forecast for the coming year, Freddie Mac predicted that rates for the 30-year fixed mortgage would fall slightly lower in the first quarter of 2020 and average 3.7 percent for the full year. Its outlook for the benchmark 10-year Treasury bond is for the yield to drift lower as well, remaining below two percent through 2021, as inflation remains a non-factor. That means borrowers looking for 15-year mortgages will be able to find sub-three percent rates for another year or more.

Most bankers expect that refinancing of mortgages will slow 25 percent in 2020, despite the lower rates. The math is simple: there are a limited number of existing mortgages to refinance and the majority of those have already been through the process. The next wave of rate-driven financing will have to be for purchases. The MBA forecasts that purchase activity in 2020 will be the highest since the peak of the housing bubble in 2006.

“I think you’ll still see some refinancing activity but the universe of consumers that

can benefit from a refinance

will continue to shrink,”

concludes Henry.

Lisa Clore observes that demand for refinancing was building at the end of 2019, rather than waning. She noted that some of the mortgages being refinanced

were originated as far back as

the Great Recession.

“I look for more people to be refinancing. It’s pretty cyclical and now the rates are down,” she says. “The rates have been staying down and I think more people are deciding it’s time to take advantage. There has been a lot of refinancing, a lot of modifications.”

This extended period of low interest rates (which will be under pressure to be reduced should a recession occur), coupled with record low unemployment, is as fertile as conditions have been for the housing market in decades. The missing ingredient is homes. Inventory of homes for sale, both in metropolitan Pittsburgh and nationwide, is unusually and persistently low. In Western PA at the end of 2019, the volume of homes for sale was enough for less than three months, according to West Penn Multi-List Service. That’s about half of the number of homes on the market than normal.

“There is a listing inventory shortage out there. There are plenty of buyers with the ability to spend more money because of low interest rates,” says Hanna. “Year over year we are up but like everyone else we are waiting for sellers to come out and list their homes. We need more new construction. That helps spur people to sell their homes.”

The key to unlocking this stagnant housing market lies with those Baby Boomers. Better health and longer working careers for that generation have led to older adults remaining longer in their family homes. Absent new product in which to downsize, Boomers have stayed put, which means fewer move-up homes have been available. Father Time is undefeated, however, and this bubble of Americans over the age of 70 who haven’t downsized is about to burst.

Such a change in supply of homes for sale, at a time when more people are working and borrowing is cheap, will make the residential mortgage banker very happy.

“One of the predictions is that we will see inventory loosen up, that there will be more homes in the market. I think that’s going to be the driver to keep loan volume going,” says Henry. “Research I read and hear suggests that the next five years we’re going to see the existing inventory of homes expand. Baby boomers are getting older and are going to start selling homes. Household formations are still running way ahead of new construction so the demand should be there.”

“I don’t anticipate rates going up any time soon so it’s just a good time in the market,” predicts Hanna. “The problem is still the housing shortage. Even if rates went up 100 basis points to where they were a year ago, I don’t think that stopped people from buying. They just realize now they can buy that much more. I look at the next five years as a very healthy housing market,” NH