If you’re waiting for a lower interest rate to buy a new home, you have probably waited long enough. There are almost unprecedented conditions in the global debt markets that have central bankers and economists scratching their heads. Lenders and debtors are paying more for loans that will mature in three months than for those that mature in ten years. In other countries – even mature economies like Germany – people buying government bonds are getting negative yields, meaning that they are paying the government for the privilege of lending the government money.

These are crazy times if you are trying to manage the assets of a bank. But if you are looking to borrow money, there has rarely been a better time to do that.

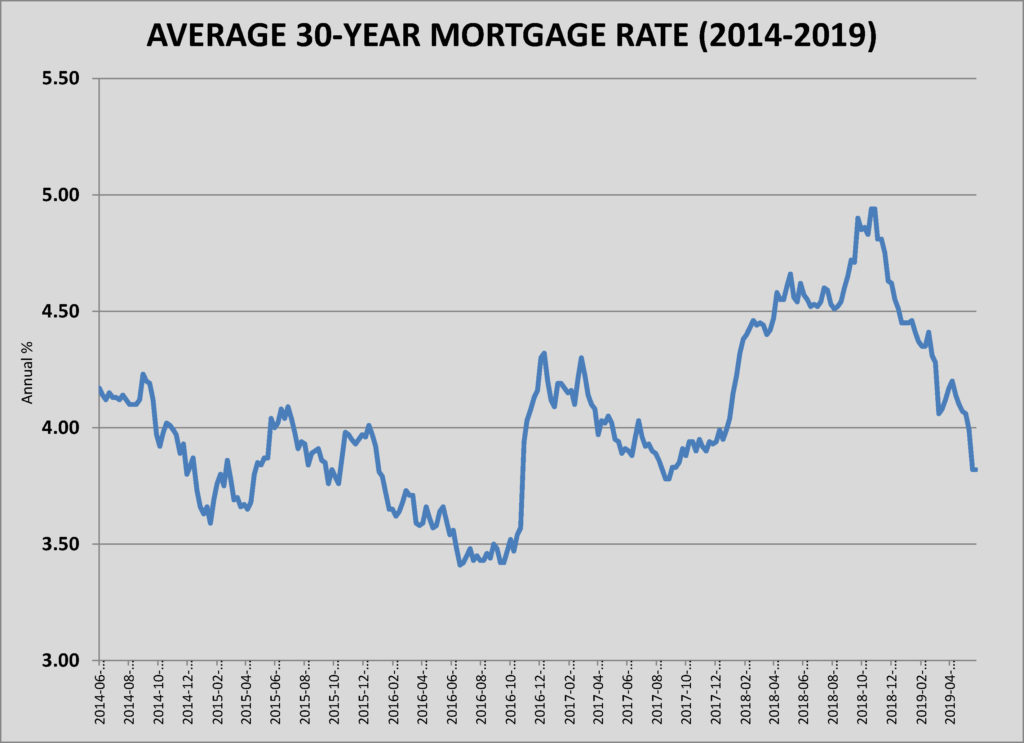

“The all-time low that I can remember for a 30-year mortgage is 3.25 percent. It’s now at 3.78 percent,” says Mike Henry, senior vice president at Dollar Bank who heads its residential lending. “A 15-year mortgage is 3.5 percent. In fact, every mortgage product we offer has a rate that begins with a three.”

Mortgage professionals are universal in their agreement about the market in 2019. Rates are going nowhere for the foreseeable future. That doesn’t mean that there won’t be a bump higher (or lower) over the next 12 to 18 months, but there is plenty of evidence to support the conclusion that borrowing costs are going to be cheap until after the next recession (whenever that may be). If you are waiting until there are more homes on the market, or more new construction, or fewer buyers, that is understandable. If you are waiting to find the bottom of the mortgage market, the wait is over.

How Did We Get Here?

The root of this somewhat upside down mortgage market is the financial crisis of 2008. The deep global recession that accompanied the financial crisis created long-term cyclical conditions that have impacted financing to this day.

Most obvious is the chilling impact the crisis had on the global economy. Recovery from the recession was unusually long and muted in the U.S., but the U.S. economy did begin to grow again by 2010. The same cannot be said for the rest of the world. Other events, like the collapse of the price of oil, have added further stress to the global economy so that few countries around the world have seen growth above one percent. Now that China and India are slowing, and with Brexit looming for Europe and the United Kingdom, the prospects for the rest of the world are dimmer for the coming year or two. All of these factors together have kept inflation low, which is a big factor in keeping interest rates low.

Inflation pushes prices higher, so lenders rightly expect that a premium is owed them by the borrower, since the value of the money loaned will be less when it’s paid back in the future. In conditions like those that exist today, interest rates are staying just ahead of inflation, which is less than two percent.

The uncertain global economy has another impact on interest rates. When governments and economic conditions overseas seem shaky, investors from all over the world look to the U.S. government for safety. This is what the phrase “a flight to quality” means. Since the yield of bonds or Treasury bills has an inverse relationship to demand for those instruments, the U.S. can offer lower interest to investors. For that reason, the interest rate on a 10-year Treasury bond was just above two percent on June 1. That is nearly a full percentage point lower than the beginning of 2018. That yield for a ten-year loan sets the market for most other loans.

This low long-term rate environment is something of a surprise to observers who expected rates to rise when the Federal Reserve Bank began raising rates and reducing its portfolio of residential mortgages in 2015. With a desire to return to a normal interest rate environment, the Fed raised the rate it charges banks to borrow money overnight by .25 percent nine times over the past three-plus years. This rate, known as the Fed Funds rate, now stands at 2.39 percent. After the last increase, in December 2018, the Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell announced that further increases would be deferred as the Fed assessed the condition of the economy. No more rate hikes are expected this year, and many observers see a cut in interest rates as a more likely next step.

“I don’t expect interest rates to go down anymore, maybe an eighth of a point, but I also don’t expect them to go any higher through this summer with the tariffs and the instability going on across the world,” says F. Duffy Hanna, president of Howard Hanna Financial Services, the mortgage services arm of the real estate giant.

“Rates are clearly down, which is a bit of a surprise,” agrees Henry. “Mortgage rates are below four percent across all product types and they appear to be staying there. There is talk from the Fed about cutting rates because of the yield curve.”

John Augustine, chief investment officer for Huntington Bank, says that the bond markets are “screaming” at the Fed to lower its Fed Funds rate.

“What bond markets watch is two years and out. The Fed controls interest rates inside of two years, generally speaking. The bond market controls rates from two years to 30. What the bond market is telling us right now is that the Federal Reserve should do one or two rate cuts this year,” Augustine notes. “The Fed is saying in comments from multiple members, that they see the signals coming from the bond markets. They understand the potential stress to the economy from the trade wars; however, they just don’t see enough economic weakness in the data to warrant a rate cut. But it’s something they are watching.”

Augustine says that bad news from the labor markets, or little progress in trade negotiations on one or more fronts would put pressure on the Fed to at least reverse the December 2018 increase, which alarmed the stock market into a big decline. He says the bond markets are pricing in a 68 percent chance of a rate cut in July and a 94 percent chance of a cut by September. Augustine also sees the bond market sending clear signals that it expects rates to remain low.

“The thing to watch is that 2-year Treasury bond, which is at 1.84 percent,” he says. “”The bond market is saying that’s where the Fed Funds rate should be in two years.”

What’s Driving the Housing Market?

When short-term rates began to rise, as the Fed increased its overnight bank borrowing rates, there was logical concern that the bump in short-term interest rates would push 30-year mortgage rates higher. Aside from the impact on affordability, one of the downstream fears was that higher rates would ultimately slow down home value appreciation, which had been recovering at an accelerated pace from the housing crisis in the late 2000s. Neither of those concerns has proven to be valid through the summer of 2019.

“Our calendar year started out slow, but by mid-April, May and June, our business really heated up,” says Mike Mooney, Western Pennsylvania market president for WesBanco. “Our volume is outpacing last year. It’s been very steady. What we are hearing is that the inventory of homes to sell is too small.”

“Our application volume really started to take off from March to April. Our volume of new mortgages and home equity loans is higher year-over-year. We measure in terms of the pipeline of loans that are in process but haven’t closed and that’s as high as it’s been in two years,” says Henry. “That may be an indication of seasonality but it is also a product of low rates.”

Interest rates have fallen far enough, especially for long-term debt, that there has been a revival of activity in refinancing. The interest rate on a 30-year mortgage fell more than two points from June 2009 to November 2012, sparking a wave of refinancing of debt that helped banks rebound and homeowners to dramatically improve their balance sheets. Rates on the 15-year mortgage fell as low as 2.7 percent during the winter of 2012-2013. Many homeowners saw their interest rate nearly halved by refinancing pre-recession 30-year mortgages to 15-year mortgages in 2013. Another round of declines hit during late 2015, after rates floated higher in 2014. The few residential and commercial borrowers who hadn’t already refinanced took advantage of the market during that second rate drop.

Bankers had correctly assumed that there were few refinancing opportunities left, but the recent decline in rates is spurring demand.

As for the derivative decline in home appreciation, there has been a slowdown in price growth across the U.S. since the latter part of 2017; however, the culprit has not been interest rates. There are structural issues in the market, like higher costs and unusually low home ownership rates among younger adults, which are cooling off demand for home sales and new construction. The lower demand translates into less price appreciation. That market phenomenon has not been present in Pittsburgh, where housing prices continue to climb at a five percent pace, or higher.

“Our volume is up. There are a ton of buyers out there,” says Hanna. “I think we will continue on that pace but the issue is still the listing inventory. There just aren’t enough houses to sell.”

The most recent report from West Penn Multi-List, Inc. showed that home sales data is supporting Hanna’s and Henry’s observations about mortgage volume. Through April 30, West Penn Multi-List tracked:

- Closed sales up 3.29 percent (8,010 units in 2019 versus 7,755 in 2018)

- Closed sales volume up 3.8 percent ($1,479,086,550 in 2019 versus $1,424,880,435 in 2018)

Interest rates alone aren’t driving the market, however. In metropolitan Pittsburgh, job creation is accelerating, with a workforce that is growing in spite of a rapidly retiring Baby Boomer workforce. Solid, if unspectacular, home appreciation means that buyers can have confidence that their investment won’t decline in value. With a solid economy and a hot job market, there is strong support for home demand. Moreover, history tells us that interest rates have a muted effect on home ownership.

For more perspective, look at how today’s rates stack up against recent and long-term environments. Factors such as the perception of risk and the interest in investors in long-term residential mortgage debt pushed 30-year rates to 4.95 percent in February 2011 and rates were as high as 4.46 percent in December 2013. The Fed Funds rate was one full percentage point lower during both of those periods. Of course, compared to history, these kinds of rates are incredibly low. Interest on a Freddie Mac 30-year mortgage was 10.13 percent in 1990 and in the peak of the housing bubble, in July 2006, 30-year rates were 6.76 percent.

What should be the main takeaway from an examination of the interest rate history is the relatively low impact of interest rates on demand, as long as the rates are within a reasonable range of incomes. When Fed Chair Paul Volcker ratcheted interest rates above 20 percent to knock down a decade-long battle with inflation, that cure crushed housing demand but in recent years changes in the interest rate of two or three percent haven’t influenced the market. The 2006 interest rate high water mark also coincided with the year the most new housing units were built during that business cycle. Double-digit interest rates would certainly make homes less affordable and knock some potential buyers out of the market; however, the interest rate outlook for the next few years is for rates to remain at or below four percent.

Another facet of post-crisis financing was the regulation and reform of the lending industry. The practices that created the housing bubble and collapse cleared out the fly-by-night originators. Many of the lenders that were burned by the crisis left mortgage lending. Those that remained operated under the increased regulation of the Dodd-Frank Act, which put strict limits on how much banks had to reserve against losses and set tight underwriting standards. Even as borrowing lagged throughout the early 2010s, lenders were either constrained by Dodd-Frank or resisted the temptation to take higher risks to make more loans to less-qualified borrowers. That self-discipline seems to be holding, even as the Trump administration loosens regulations.

“I think standards have held. Lenders learned their lesson from the great recession. If a borrower is not qualified they are not getting a loan,” says Hanna.

A low interest rate environment enables the housing market, which in turn provides a strong foundation for the economy. Like most cities, Pittsburgh has seen a lower home ownership rate among younger residents, so-called Millennials, than for previous generations. Unlike few other cities, Pittsburgh has become a haven for Millennials, as excellent job growth in emerging technologies and industries is attracting more young professionals. If borrowing costs remain near historic lows, Pittsburgh’s reasonably affordable housing stock may be an incentive to push more Millennial renters into buying.

Livability, a website that tracks and catalogs what people like about where they live, recently ranked Pittsburgh as the best city for first time home buyers. The study found that 82.9 percent of the homes on the market in Pittsburgh could be afforded by a family earning the median income in the region. Livability listed the median home price at $171,000 in Pittsburgh, a far cry from the $1.3 million median price in San Francisco.

The rise of the middle class is arguably what separates the American experiment in democracy from other nations. One of the key building blocks to a healthy American middle class was the 30-year mortgage, which allowed working families the opportunity to own their own homes while they were raising children. The stability of the middle class has been threatened as family-sustaining working class jobs have declined over the past few decades. The Pittsburgh economy has fared better at creating and retaining those kinds of jobs in this new century, as well as attracting higher-paying jobs. The outlook for maintaining such an important economic building block as home ownership is brighter when financing a home remains accessible to those who want to buy. By all indications, interest rates will support accessible borrowing well into the next decade. NH